Axel Alstrom in his trading post with his granddaughter Augusta, about 1949.

Axel Alstrom in his trading post with his granddaughter Augusta, about 1949.

Essay by Alice Alstrom-Henderson, Orienne Reich, and Deborah Schildt

Winter 2022-23, FORUM Magazine

Each day is a journey, and the journey itself is home. —Matsuo Basho

CLOSE YOUR EYES. Imagine a young man setting sail from Gothenburg, Sweden, in the spring of 1913. He left behind grandparents, parents, 14 siblings, and two centuries of family farming to try his luck at something new—something more. Gazing off the deck of a Swedish American Line Steamship and into the eyes of Lady Liberty, young Axel Alstrom may have harbored many doubts, but the years that followed would hone his dreams and forever change the landscape of his life.

Alice Alstrom-Henderson became a part of that landscape. “Axel was my grandfather. He was born into a very large farming family in Borgstena, Sweden,” she says.

The Alstroms farmed during a period in history that used human brawn for the hard, manual labor required in agricultural production. After arriving in the United States, Axel worked on a farm in Massachusetts for a few years, or perhaps only a few months. Other Alstroms were living in America at that time—Axel’s relatives. He sought them out in Tacoma, Washington before destiny drew him to the far north near Dawson, where he was enticed by talk of gold. The last leg of that journey was by a sled team drawn by 11 dogs and a wolf. His letters home reference Whitehorse, Skagway, and a Swede he worked for in Flat, Alaska as he traveled to the western part of the Last Frontier.

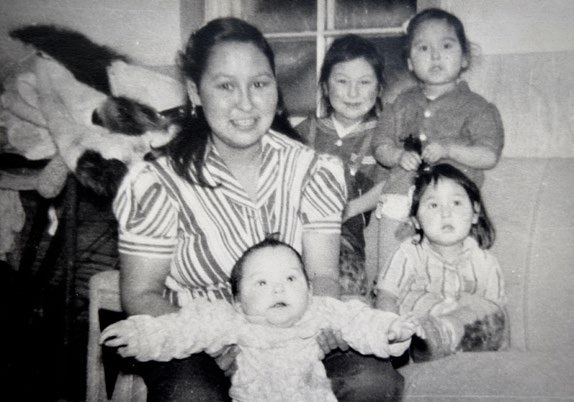

Alice Alstrom-Henderson, Elizabeth, Torgny, and Augusta.

Alice recalls her earliest memories of Axel. “My sisters and I grew up on the lower Yukon River and were raised by our grandmother in Fish Village. Fish Village is now uninhabited. I remember Grandpa as a big man who always gave us candy from his store.”

But to be honest, Alice learned more about him through her relatives in Sweden than from her early childhood memories. “Those memories lie within my blood, but my Swedish relatives are the ones who have documented our shared family histories patched together from letters my grandfather wrote about his new life in Alaska.”

Alice’s cousin Torgny Alstrom, who lives in Sweden, was bitten with curiosity and contacted her. “I had never had a big interest in the life of my immigrant grandfather. Probably my childhood was so overwhelmed by survival as an orphan that my personal history was ephemeral. Torgny’s interest has since magnified my perceptions.”

Records show Alice’s immigrant grandfather served as a paramedic during World War I in St. Michael’s and continued his caretaking of village people during the Spanish Flu epidemic. He claimed that he did not get the flu because he used snuff. “Grandpa Axel earned his citizenship because of his service in the U.S. military,” she’s been told.

Molly with Augusta, Anna, Alice, and Elizabeth, about 1949.

Being out there, the Northern Commercial company picked up his energies for a while, but he started his own trade in furs and fish in Kwiguk and moved down to Alakanuk, at the mouth of the Yukon Delta. “He began trading commodities to local folks and eventually had coins minted for the budding economy,” Alice says.

Stories claim that Axel lent and lost money to the frequently visiting aviators. His trading center became a gathering place for people in the area. Aside from the trade, he showed movies to the locals.

Axel married a Yup’ik woman, Anna Strongheart. “I don’t know much about her, except that she was mother to my father, Ole, and his twin brothers Frank and Fred.” Anna died early, and Axel remarried Ledwina Oney, who was also Yup’ik and had worked in Axel’s home. Axel and Ledwina had an adopted daughter, Mary, who also lived a short life.

“Grandpa Axel’s desire was for his sons to have an education. I’ve heard that he provided for the construction of a school in the area. My father seemed to align with formal schooling and quickly became his father’s right-hand assistant. He learned to fly at an early age, as did his twin brothers. After some years of experience in the family’s business, he went to Seattle to buy for the trading post. “In those days, you could fly on Pacific Northern [Aerospace Alliance, PNAA] from Anchorage to Seattle, in a DC-4, with maybe a stop in Yakutak and Ketchikan, then on to Seattle all in about five hours,” says Alice.

Ole Alstrom in the early 1950s.

“The Swedish relatives speak of Axel’s grief for his children, whose mother had died,” Alice says. Axel tried to comfort his boys by buying them airplanes, toys of a sort. He wrote of their talents in aviation in a letter to Sweden, “The twins could land a plane on a plate, but sometimes they also ended up outside the plate.” The Alstrom brothers were to become some of the first certified Native pilots in the Territory of Alaska.

“My life was shadowed by the deaths of my father Ole, mother Molly (Westdahl), and our youngest sister Helen in 1955. My father’s plane crashed across from St. Mary’s, near the mission on the bank of the Andreafsky River,” Alice says. Ole had set up another store in St. Mary’s, an extension of the Alstrom Trading Post in Alakanuk. Their plane was filled with cargo. “The four of us left behind were raised by my grandmother, Teresa Westdahl.”

“Gramps created an adventure of many lifetimes: an expedition into the future of the Great Land. Today as I think about my history, I can say I am Yup’ik, and I have developed a fondness for both sides of my history. I thank my Swedish relatives for searching us out. You have come and gone down the Yukon River to discover a part of your past. In return, we have gone to Sweden to find our Swedish family’s welcome mat greeting us with open arms and hearts,” Alice says.

Pilots Fred and Frank Alstrom.

This historically recent Viking, Axel Alstrom, and his Yup’ik partners—Anna Strongheart and Ledwina Oney—co-created a well-touted legacy. Teachers, city managers, and corporate leaders with a huge tilt towards fisheries are actors on this great stage. “Up and down the rivers, there are well-known family names with a history similar to my own,” says Alice.

One can go to any town in Alaska and hear stories of mythic proportion—reconstructed histories of our coming to be—in different languages spoken alongside the various indigenous tongues. And they always resemble “e pluribus unum, my grandfather’s welcome to this country,” Alice says.

Grandfather Axel died in 1950. He is buried alongside his old friend Jack Lamont, a French-Canadian/Alaskan, in Mountain Village, a remote Yup’ik village tucked midway between Alakanuk and St. Mary’s. Mountain Village lies along the banks of the mighty Yukon River—the trade route that served Axel Alstrom so well.

Rest in peace, Axel Alstrom. Your memory is carried in this welcoming land. ■

Alice Alstrom-Henderson, Orienne Reich, and Deborah Schildt began their collaborative storytelling twenty years ago when they produced, along with Bea Adler, the documentary film “Unraveling the Wind.” The film featured the achievements of Alice’s uncles—twin brothers Fred and Frank Alstrom—who were among the first Alaska Native pilots. Torgny Alstrom, a resident of Sweden, came across the documentary on the Internet in 2015. This story originates from that documentary and addresses what happened after Torgny sought out his cousin Alice Alstrom-Henderson in Alaska and brought her to embrace and explore the history of their extended family. The authors thank Elizabeth Alstrom and Matilda Alstrom-Oktoyak for their help with photos and research for this article.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

November 13, 2025 • MoHagani Magnetek & Polly Carr

November 12, 2025 • Becky Strub

November 10, 2025 • Jim LaBelle, Sr. & Amanda Dale