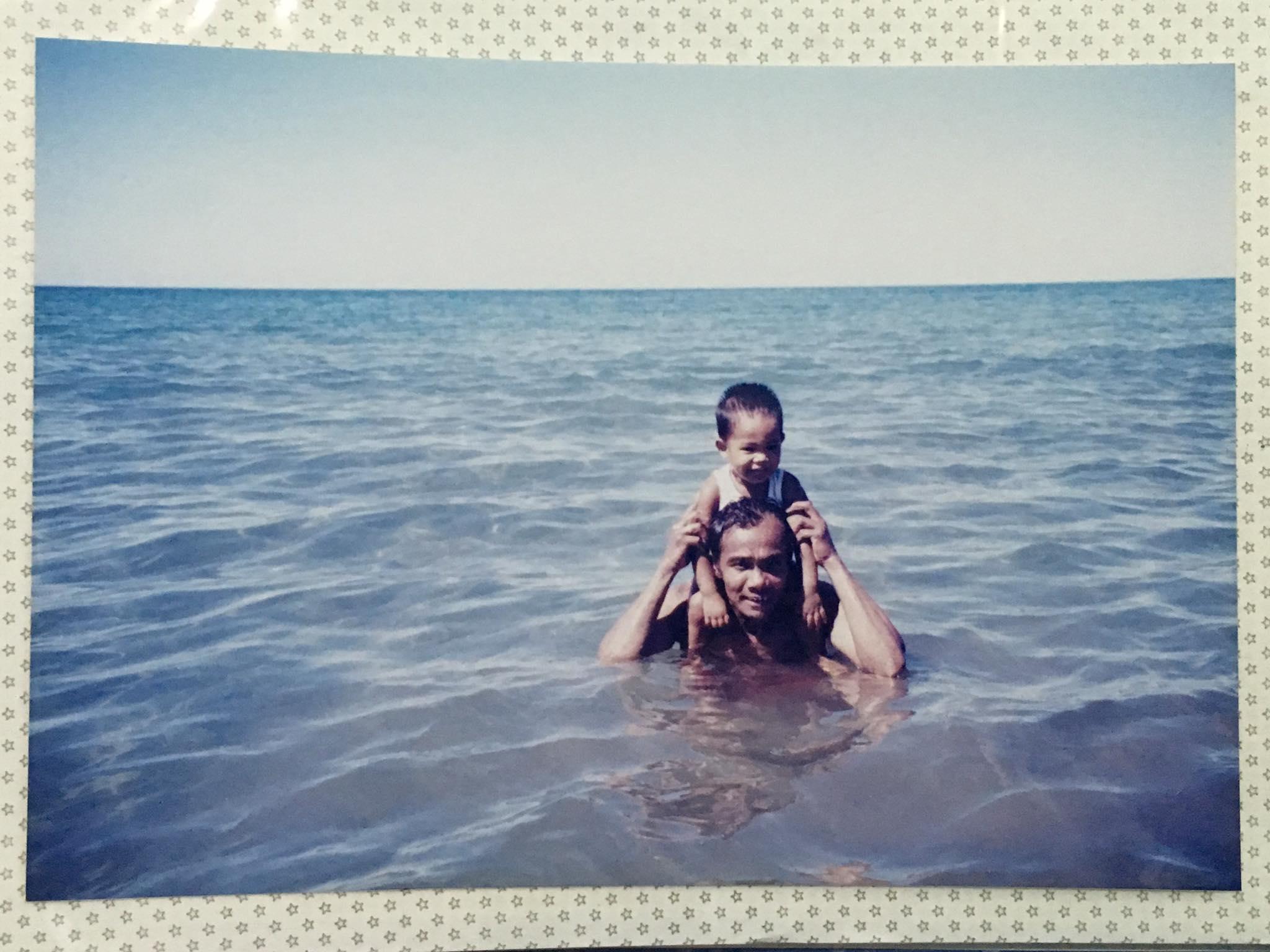

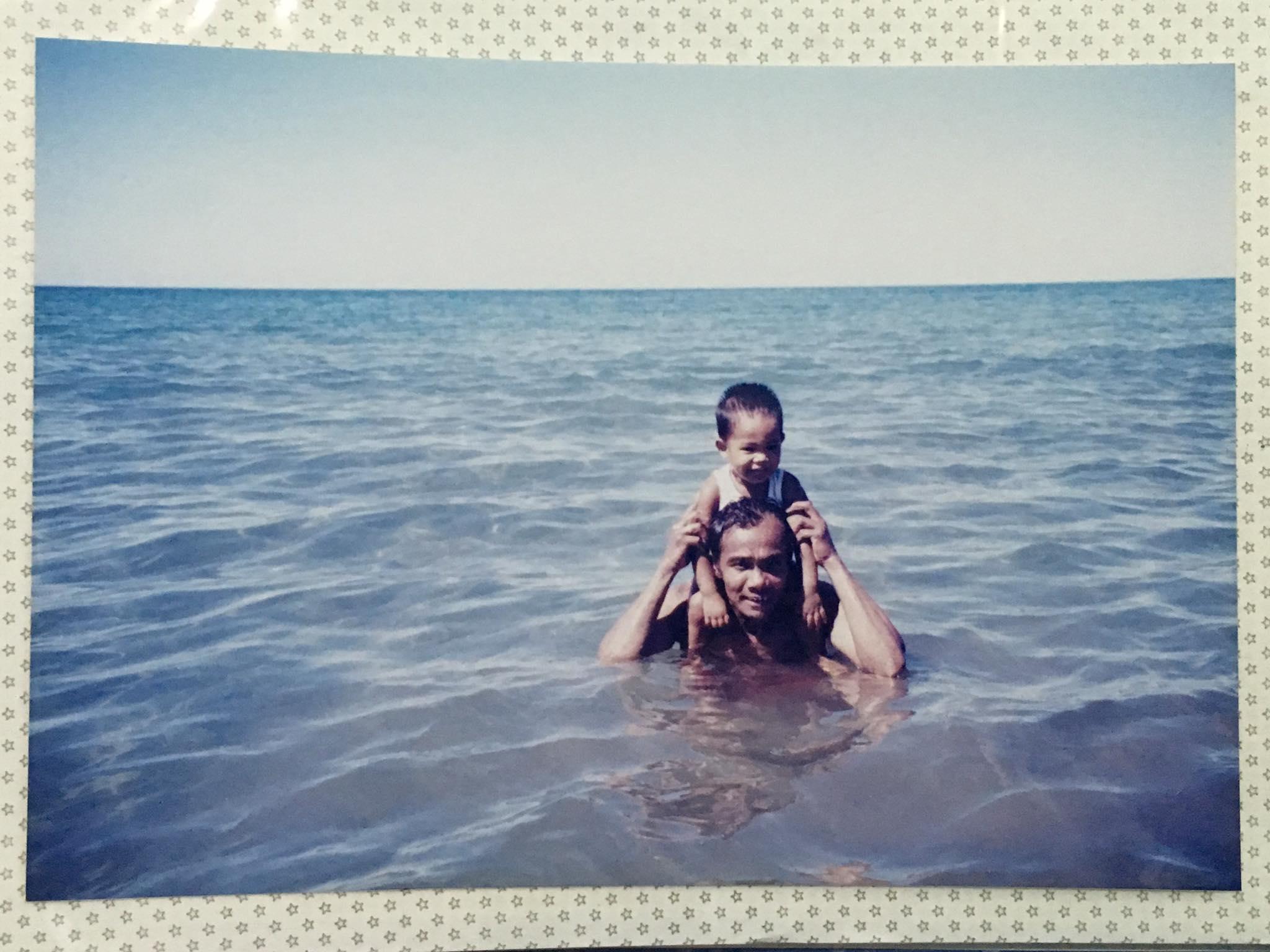

Rafael, at 1-year-old with his dad, Patrick, swimming in Pangil Beach.

Rafael, at 1-year-old with his dad, Patrick, swimming in Pangil Beach.

By Rafael Bitanga

Winter 2024-25, FORUM Magazine

MY CHILDHOOD WAS A DELICATE BALANCING ACT, straddling two starkly different landscapes - the lush tropics of my birth country, the Philippines, and the cold, rugged terrain of Kodiak, Alaska. Both places left indelible marks on my identity, shaping me into who I am today. The journey to reconcile these disparate realities was not easy. It was fraught with tension and inner conflict as I struggled to find my place in these two worlds. But through this struggle, I gained a profound understanding of my dual heritage, learning to appreciate each culture's unique beauty and richness.

In Laoag City, Philippines, the scent of saltwater was a constant companion, mingling with the distant rush of the Currimao River rapids flowing out to the West Philippine Sea. The air, thick with humidity, carried the sweet fragrance of ylang-ylang flowers and the earthy aroma of rice fields after a fresh rain. The constant buzz of cicadas provided a rhythmic backdrop to daily life, punctuated by the cheerful calls of the Maya birds flitting between the mango trees.

At age six, I have vivid memories of walking along the coral coast of Currimao when I lived in the Philippines, my bare feet sinking into the warm, fine sand. The beach was a treasure trove of natural wonders, and I spent countless hours exploring its riches. I would gather umang (hermit crabs) washed ashore by the tides, marveling at their ability to make homes from discarded shells. The tide pools were miniature ecosystems teeming with life—tiny fish darting between swaying anemones, brittle starfish hiding under rocks.

The ocean's bounty provided sustenance for our community. It has connected us to previous generations who fished the same waters and hauled in the nets heavy with the sea's offerings for millennia. I would watch in awe as the fishermen returned at dawn, their outrigger canoes laden with a kaleidoscope of fish—from the silvery-blue of mackerel to the vibrant red of snapper. The fish market was a cacophony of sounds and smells, with vendors calling out their prices and the pungent aroma of bagoong (fermented fish paste) wafting through the air.

Our daily lives revolve around the rhythm of nature. I would accompany my mom to the local market in the early mornings before the tropical heat became too intense. The vibrant colors of fresh produce—deep purple eggplants, bright green bitter melons, and fiery red chili peppers—created a visual feast. Ma would haggle good-naturedly with the vendors, exchanging gossip and laughter as she filled her basket with the day's ingredients.

Back home, the kitchen was the heart of our household. The sizzle of garlic and onions hitting hot oil, the aromatic steam rising from pots of sinigang (sour tamarind soup), and the sweet scent of bibingka (rice cake) baking in banana leaves created a sensory tapestry that defined my childhood. Family gatherings were frequent and boisterous, with aunts, uncles, and cousins crowding around the table, sharing food and stories late into the night.

The Filipino concept of 'kapwa'—a shared inner self—was not just a philosophy, but a way of life. Neighbors were like extended family, always ready to lend a hand or share a meal. Children played freely in the streets, inventing games with whatever was at hand—rubber slippers became makeshift bowling balls, while empty cans were repurposed as bowling ball pins.

This was the world I knew—warm, vibrant, and deeply interconnected. It was a place where the boundaries between family, community, and nature seemed to blur, creating a sense of belonging that encompassed not just people but also the land and sea that sustained us.

The Filipino concept of 'kapwa'—a shared inner self—was not just a philosophy, but a way of life.

When I emigrated to Kodiak, Alaska, at eight years old in 2009, it felt like stepping into another world entirely. My mom, older sister, and I moved to Kodiak to join my dad, who has been in seafood processing since the 1980s. The lush tropical landscapes I had known were replaced by a rugged, untamed wilderness that both awed and intimidated me. I was immediately struck by the dramatic rivers and inlets carved by glaciers and the towering green mountains that rose from the ocean's edge, their peaks capped in snow even in summer.

The air in Kodiak was crisp and clean, carrying the scent of pine and salt spray. Instead of the constant warmth I was accustomed to, I experienced the sharp bite of cold for the first time. The changing seasons were a marvel to me—the explosion of wildflowers in spring, the long, light-filled summer days, the golden hues of fall, and the silent, snow-blanketed winter landscapes.

The wildlife of Alaska was unlike anything I had ever seen. I watched in awe as brown bears foraged along the rocky shoreline, their massive forms dwarfing everything around them. Bald eagles soared overhead, their piercing cries echoing across the bay. In the waters, orca and humpback whales breached the icy surface, sending plumes of mist into the air. The salmon runs were a spectacle that never ceased to amaze me—thousands of fish fighting upstream to spawn in the rivers of their birth, their determination a testament to the power of nature.

The raw, untamed natural beauty was breathtaking yet felt utterly foreign to my young eyes accustomed to the gentle, undulating landscapes of the tropics. The sheer scale of the Alaskan wilderness was overwhelming at first. The mountains seemed to touch the sky, and the forests stretched as far as the eye could see. While familiar in its constant presence, the ocean was a deeper, darker blue than the tropical waters I knew, its mood more mercurial and its power more evident in the crashing waves and swirling tides.

As I grappled with the challenges of adapting to my new life in Alaska, I was caught between two worlds. I was just another local boy in the Philippines, blending seamlessly into the crowd. But in Kodiak, I was an outsider; my brown skin and accented English set me apart from my peers. Everything about me, from my clothes to my food, seemed to underscore my foreignness. This struggle to reconcile my two identities was an emotional journey filled with moments of self-doubt and a longing for acceptance.

The challenges of adapting to my new environment were physical, deeply emotional, and social. I longed for the familiarity and comfort of my homeland, even as I marveled at my new surroundings. Finding my place in this new world was fraught with difficulties, and there were many moments when I felt lost between two cultures, belonging fully to neither.

I remember one particularly challenging day in third grade. It was lunchtime, and I had brought a container of pinakbet—a traditional Filipino dish of stir-fried vegetables in fish sauce with crispy pork and rice. As I opened my lunch, the rich aroma wafted through the air, drawing attention from my classmates. One boy wrinkled his nose and loudly proclaimed, "Eww, what's that weird smell?" Another chimed in, calling my food "gross" and "smelly."

I felt a hot rush of shame and anger course through me. The food that had always been a source of comfort, that reminded me of home and family, was suddenly a mark of my otherness. I wanted to lash out and defend my culture, to explain the significance of the dish and how it connected me to my roots. But the words stuck in my throat, choked by embarrassment and a desperate desire to fit in.

What hurt even more was the reaction of my Filipino peers. I had expected them to come to my defense, to stand up for our shared culture. Instead, they joined in, distancing themselves from me and my "smelly" lunch. Some even exaggeratedly plugged their noses, laughing along with the others. At the time, it did not make sense to my young mind why they would turn against me and our culture.

This experience was a turning point. In the following days, I begged my mother to pack me "American" lunches—peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, cheese sticks, and apple slices. I stopped speaking Ilocano at school, even with other Filipino students. I tried to change how I dressed and talked, anything to blend in and avoid standing out.

At home, I found myself pushing away the Filipino parts of my identity. I resisted speaking our native language, refused to eat traditional foods, and showed little interest in cultural celebrations. My parents were bewildered and hurt by this sudden rejection of our heritage, but I couldn't articulate the complex emotions driving my behavior. I was caught in a painful cycle of trying to erase parts of myself in a misguided attempt to gain acceptance.

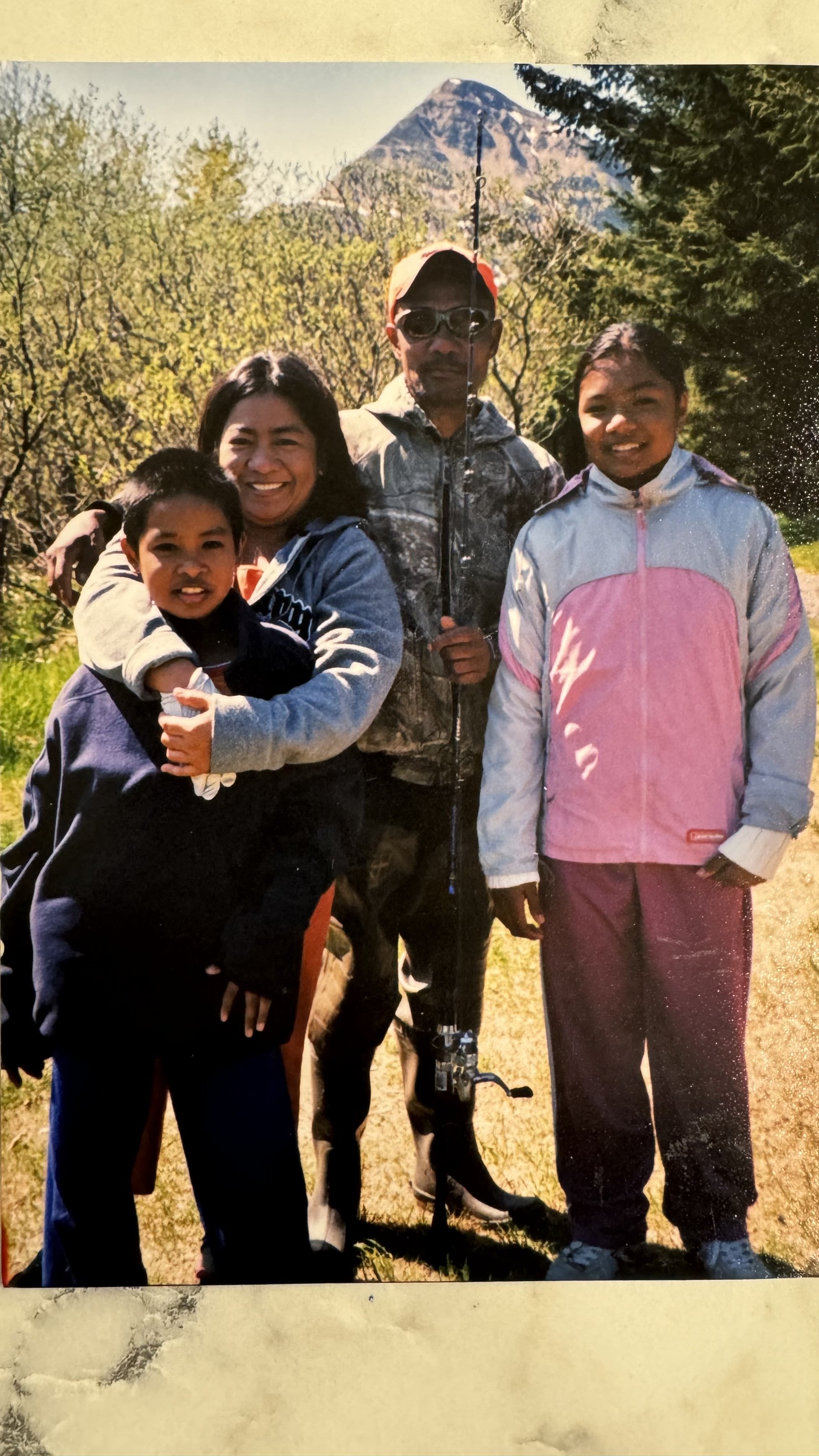

Rafael was with his family at age 22. Fourteen years after moving to the United States, Rafael returned to the Philippines to visit his family.

The internal conflict was exhausting. I felt guilty for turning my back on my culture, yet I was desperate to fit in with my new peers. This struggle affected my self-esteem and academic performance. I became quieter in class, hesitant to speak up for fear of drawing attention to my accent or saying something "un-American."

In fifth grade, I found the courage to be more involved with the school, engaging in activities such as serving as the student government president. Whether this title resulted in this change or not, my peers changed how they perceived me—seeing that a brown-skinned Filipino could also serve as student government president. This experience was a revelation. It showed me that I could be accepted for who I was and that my differences could be a strength rather than a weakness.

While none of the people who mocked my food ever apologized, looking back at this experience, I empathize with my Filipino peers who turned against our people in their pursuit to be more American and also more accepted. I realize now that they were likely grappling with the same insecurities and pressures I was, trying to navigate the complex waters of cultural identity in a new land.

As I slowly adapted to life in Kodiak, I began to find parallels between these two disparate places I called home. My first home in the Philippines was nurtured by the Currimao River, whose waters irrigated the rice fields that had fed our community for centuries. In Kodiak, I soon discovered that the local streams and rivers held similar significance, providing the salmon runs that are the lifeblood of the island's economy and culture.

Over time, I began to see other similarities. Though the particular species of fish differed, the communities in both lands shared a rhythm and lifestyle intimately tied to the ebb and flow of the waterways. Like those in Laoag, the fishermen in Kodiak lived by the tides and seasons, their livelihoods dependent on their deep understanding of the sea.

While expressed differently, the sense of community was strong in both places. In Kodiak, neighbors came together for potlucks and community events, sharing food and stories like in the Philippines. The concept of "Bayanihan"—communal unity and cooperation—that I knew from my homeland echoed in the way Alaskans pulled together during harsh winters or emergencies.

Even as I tried to suppress my roots, the land seemed to call me back. When I struggled to integrate my Filipino identity into my new Alaskan context, I often retreated into the solace of nature to reflect. I was drawn to the shoreline, much as I had been in the Philippines. Watching the endless cycle of the tides, the water rushing in and pulling back in an eternal dance, helped ground me. The vast and unchanging ocean became a bridge between my two worlds.

I learned that Filipinos often move to Kodiak, Alaska, due to job opportunities in the fishing- and seafood-processing industries. This migration pattern has historical roots dating back to the early twentieth century when Filipino workers were recruited for salmon canneries. Over time, this attracted new immigrants through family and social networks. The combination of economic opportunities, cultural similarities in coastal living, and an established Filipino presence makes Kodiak an attractive destination for some Filipino immigrants. This knowledge helped me feel part of a larger story, a continuation of a journey that many had undertaken before me. It gave me a sense of belonging to a community with deep roots in this seemingly foreign land.

As I approached my sophomore year of high school, a pivotal moment in my journey of self-discovery occurred. My sister, four years older than me, had begun attending Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. During one of her returns to Kodiak, she shared readings like "Brown Skin, White Minds" by E. J. R. David and learnings from her classes. These discussions opened my eyes to the experiences that had led me to reject my Filipino culture.

Rafael at eight-years-old, his mom Juliet, dad Patrick, and older sister, Deborah at Buskin River in 2009 when they first arrived in Kodiak, Alaska.

Buoyed by readings from my sister and my newfound perspective, I embarked on a project during my senior year of high school. I interviewed Filipino community members, seeking to understand their experiences and the history of our community in Kodiak. These conversations were eye-opening and healing.

Ms. P, a retired elementary school teacher, shared a deeply resonated insight with me. She explained that often when Filipinos immigrate, they experience the brutality of having their community turn its backs on them to find belonging and move up in the new community. In turn, the cycle of bringing our culture down is perpetuated instead of finding strength in having new Filipinos join the community.

This helped me understand and forgive my Filipino peers who had mocked my lunch years ago. Like me, they were caught in a cycle of assimilation and self-rejection. Ms. P's words also gave me the courage to break this cycle, embrace my heritage fully, and help create a more welcoming community for future immigrants.

I connected these struggles to the natural world around me. As salmon fight upstream against powerful currents to return to their spawning grounds, I needed to find the strength to embrace all parts of myself, swimming against the currents of assimilation to reclaim my cultural identity.

With this new understanding, I began to actively bridge my two worlds. I started bringing Filipino dishes to school potlucks, proudly sharing the flavors of my homeland with my peers. To my surprise, many classmates were curious and appreciative, eager to try new foods and learn about Filipino culture.

I joined the Kodiak Filipino American Association, connecting with a community of hundreds of Filipinos who wanted to celebrate or had finally built the courage to celebrate our heritage. It was hard to believe it took decades to build up this community, especially because Filipinos make up over 30 percent of Kodiak's population. The slow development likely stemmed from early immigrants' focus on work, the pressure to assimilate, and the challenges of organizing in a remote location.

Participating in cultural events and celebrations helped me reconnect with the traditions I had pushed away. At home, I began to embrace the parts of my culture I had once rejected. Determined to keep these culinary traditions alive, I asked my parents to teach me to cook Filipino dishes. The smell of bagoong (fermented, salted fish and shrimp) in our foods, which had once embarrassed me, became a source of pride and nostalgia.

When I attended Cornell University for college, I was shocked and delighted that they offered Filipino history courses. These classes helped further my journey of reclaiming my Filipino identity. I learned about the complex history of the Philippines, its struggles with colonialism, and the resilience of its people. This academic exploration of my heritage gave me a deeper appreciation for the strength and perseverance within my family.

During breaks from college, when I returned to Kodiak, I found solace in the natural world. I hiked the mountain trails, kayak in the bays, and sat by rushing streams, recognizing that the land held wisdom about resilience, adaptability, and thriving in the face of change. The Alaskan wilderness, which had once seemed so foreign, had become a part of me, teaching me lessons about strength and survival that echoed the stories of my ancestors.

Thirteen years after arriving in Kodiak, I returned to the Philippines as an adult to visit my extended family. The moment I stepped off the plane in Manila, the warm, humid air enveloped me like an embrace, carrying the familiar scents of my childhood—a mix of tropical flowers, street food, and the ever-present hint of the sea. I watched the landscape unfold through the car window as we drove from Manila to Laoag City. The capital's crowded streets gradually gave way to lush countryside, with rice paddies stretching to the horizon, their emerald shoots swaying gently in the breeze. Palm trees lined the roads, their fronds rustling in the warm wind, a sound that had once been the backdrop to my daily life.

At that moment, stirring the pot of sinigang and bridging my two worlds through stories, I felt a profound sense of peace.

Memories came flooding back at the first sight of the rice terraces watered by the Currimao River. The stepped fields, carved into the hillsides generations ago, were a testament to the ingenuity and perseverance of the Filipino people. I remember walking with my grandfather in these fields as a child before he passed away, and my small hands were learning to uproot sugar cane in the muddy water.

The reunion with my extended family was joyous and overwhelming. Aunts, uncles, and cousins I hadn't seen in over a decade engulfed me in hugs, exclaiming how much I'd grown. Their rapid-fire Ilocano, punctuated with laughter and affectionate teasing, washed over me. At first, I struggled to keep up, my tongue stumbling over words that had once come so naturally. But as the days passed, the language of my childhood returned, and each remembered phrase felt like a rediscovered treasure.

One evening, I felt emotionless as the sun set over the rice fields, painting the sky in vibrant oranges and pinks. The beauty of this place, the depth of its history, and the strength of the connections that tied me to this land came rushing in. I realized that although I had physically left the Philippines, it had never left me. It lived in my memories, values, and how I saw the world.

Even from thousands of miles away, Alaska's soaring glaciers and mist-shrouded mountains carved figurative grooves into my mental landscape, and I thought of them often while visiting the place of my birth. The contrast between the two landscapes was stark, yet I found myself drawing connections. The resilience of the Filipino people in the face of typhoons and hardships mirrored the strength I had witnessed in Alaskans weathering harsh winters and isolation.

As I helped my aunt prepare sinigang one evening, the sour tamarind broth simmering on the stove, I shared stories of Alaska with my family. I told them about the midnight sun and the northern lights, bears fishing for salmon in crystal-clear streams, and the tight-knit community that had become my second home. My young cousins listened with wide-eyed wonder, just as I had once listened to tales of snow and mountains that seemed like fantasy.

At that moment, stirring the pot of sinigang and bridging my two worlds through stories, I felt a profound sense of peace. I realized that my dual identity, which had once been a source of conflict, was now my greatest strength. I could move between these two worlds, carrying the best of both.

As my visit to the Philippines ended, I reflected on the journey that had brought me to this point. The struggles I had faced in reconciling my Filipino heritage with my Alaskan upbringing now seemed like necessary steps in forging my unique identity.

I have learned that home is not rooted in a single physical place but lives within my experiences' rich tapestry. It exists in the memories triggered when I cook the Filipino dishes of my youth, walk through coastal tide pools, or see the bright fuchsia of fireweed blooming in the Alaskan tundra. Home is the warmth of family gatherings in Laoag and the camaraderie of community events in Kodiak. It's the rhythm of waves lapping at tropical shores and the crash of glaciers calving into icy fjords.

At twenty-three years old, I've realized my dual identity is a strength, allowing me to move between worlds and connect with people from all walks of life. I can navigate the complexities of cross-cultural communication, drawing on my experiences to build bridges of understanding. This ability has become increasingly valuable in our interconnected world, where traversing cultural boundaries is more important than ever.

My journey has taught me the importance of cultural preservation and the danger of losing one's roots in pursuing assimilation. I am committed to passing on this legacy when I have children someday. I envision taking them walking on the shores of Laoag City and the beaches of Kodiak, teaching them how we are shaped by every ecosystem we inhabit.

I want my future children to know they are the product of many lands and cultures, each adding to the beautiful complexity of their identity. I will teach them to find strength in their roots, embrace the challenges of bridging worlds, and seek out the wisdom of the natural world. They will learn to make sinigang and salmon perok, dance the tinikling, and appreciate Alutiiq art. Most importantly, they will understand that their diverse heritage is not a burden to be overcome but a gift to be cherished.

As I look to the future, I know the pull of the Philippines and Alaska will never leave me. They are the magnetic poles that orient my inner compass, the lands that live within my blood and memory. These two islands, so different yet both so integral to who I am, have taught me that identity is not about choosing one world over another. Instead, it's about weaving together the threads of our various experiences and influences to create a tapestry that is uniquely our own.

Though I make my home in other terrains now, pursuing my career and continuing to explore the world, I carry these islands wherever I may roam. The lessons I've learned from straddling two cultures inform every aspect of my life—from my relationships to my professional endeavors. I am drawn to work that allows me to act as a cultural bridge, using my unique perspective to foster understanding and collaboration across diverse groups.

I am proud to be a child of two islands, forever shaped by the rivers, oceans, mountains, and jungles that raised me. My story is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the beauty that can emerge from embracing our complex identities. As I continue my journey, I carry with me the warmth of the Philippine sun and the crisp clarity of Alaskan air, reminders of the two worlds that have made me who I am. Ultimately, I've learned that the question is not whether I am Filipino or Alaskan but how I can be the best version of myself—a self that honors both heritages while forging its unique path. This journey continues to unfold, rich with challenges and discoveries, as I navigate the waters between my two island homes. ■

Rafael Bitanga is a documentary filmmaker from Kodiak Island, Alaska who focuses on the power of film and service to uplift others with dignity. Beyond film projects, he teaches filmmaking to youth and educators across Alaska through the nonprofit See Stories.

FORUM is a publication of the Alaska Humanities Forum. FORUM aims to increase public understanding of and participation in the humanities. The views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the editorial staff or the Alaska Humanities Forum.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

November 13, 2025 • MoHagani Magnetek & Polly Carr

November 12, 2025 • Becky Strub

November 10, 2025 • Jim LaBelle, Sr. & Amanda Dale