Roshier H. Creecy at his cabin in Wiseman in the 1930s or '40s. Harry Leonard, a filmmaker and friend of Creecy’s, filmed him with his dogs, sled, and gold pan. This is a still from that film.

Roshier H. Creecy at his cabin in Wiseman in the 1930s or '40s. Harry Leonard, a filmmaker and friend of Creecy’s, filmed him with his dogs, sled, and gold pan. This is a still from that film.

by M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

Winter 2023-24, FORUM Magazine

IF FOR ONLY A MOMENT, let us move away from the anthropology of societies and cultures to turn our attention to the material culture of individuals. Along the way, we will meet Roshier Harrison Creecy (1866-1948, born in Rustburg, Vir.), an African-American gold miner who lived in Alaska from 1897 until he froze to death at the age of 82 in his Wiseman, Alaska cabin. On this journey through archival collections, 20th-century film recordings, and audio interviews surrounding the life of Creecy, I will interject a bit of my own personal narrative as a means of engaging in reflexive anthropology.

In both anthropology and archaeology, artifacts are things, objects, and/or items that signify human activities. It is the assemblage of artifacts that make up the material culture that collectively gives data for extraction and interpretation.

Therefore, within this framework, we are offered an opportunity to escape the pitfalls of generalizations and boxing individuals into categories they may or may not adhere to. Yes, it is important to know Roshier Creecy was an African American and veteran of the Indigenous Assimilation Era Wars (1887-1934). However, there is more to learn about his life without implying the impact of structural and systemic racism on his life. I am at a place in my own journey where it means little to me to say that I am an African-American transgender woman because there are other dynamics of my personhood I would rather uplift in conversation, such as my identification as a cultural anthropologist and historical archaeologist, because these identities of mine are the driving forces of this essay.

After my presentation about Afrofuturism at the Alaska Anthropological Association’s annual meeting in Spring 2023, Crystal Glassburn, an archaeologist from the Bureau of Land Management, pulled me aside to speak about Roshier Creecy. I had never heard of Creecy, but because my presentation illustrated my research interests in the Buffalo Soldiers of Skagway, the African-American soldiers who built 60% of the Alaska-Canada Highway (ALCAN), and 20th-century women entrepreneurs Bessie Couture and Zula Swanson; Glassburn thought I would be a great candidate to pick up Creecy’s trail for a potential future project that involves developing an interpretive kiosk at the Arctic Interagency Visitor Center in Coldfoot, Alaska for visitors to learn about Roshier Creecy.

I first read about Creecy from a Pioneers Hall of Fame website link that supplied enough information for me to learn more about the history of placer mining in Alaska. However, what really piqued my interest was a narrative of an African American’s journey to Alaska that had nothing to do with the military or work on the Alaska pipeline, but rather a story about an individual who arrived in Alaska for the purpose of gold mining during the Klondike Gold Rush (1896-1899).

Film showing Roshier H. Creecy at his cabin in Wiseman in the 1930s or '40s. Harry Leonard, a filmmaker and friend of Creecy’s, filmed him with his dogs, sled, and gold pan. (Alaska Film Archives - UAF)

At the onset of this research project, a colleague asked if I was concerned about being tokenized. I get it. I respect my friend’s awareness of the circumstances. I replied, “I am a trailblazer,” the first time I ever spoke that word out loud about myself. In the past, my reluctance to say I was a trailblazer came from my desire to remain humble and not see myself as extraordinary in being the first Black to do this or the first Black to do that. Yet in this situation, I know there are no other diasporic African transgender women archaeologists in Alaska with an interest in documenting the stories of diasporic African descendant people in the Circumpolar Far North. It’s just me out here on the land conducting archaeological investigations and being an ethnographer in search of human stories and cultures. I know who I am in this space and where I am going. Can I be tokenized as the exceptional other when I’m driving this ship or is this just another case of Ralph Ellison’s unnamed protagonist in his 1952 novel “The Invisible Man?”

I ask this question not solely for my personal journey, but because I want to know if Roshier Creecy felt the same way over a hundred years ago as the owner of the Eureka Creek Roadhouse he bought in 1904 and his multiple prospecting claims throughout the Alaska Klondike-Koyukuk region. I wondered if Creecy had agency. How did he negotiate power? The material culture, and the collection of items/artifacts he left behind informs me that he staked his claims, he inquired and defended his Veterans Administration benefits, and he considered his age and loneliness as he prepared to die.

The only historical biographical sketch solely dedicated to Roshier Creecy is, “Roshier H. Creecy: A Black Man’s Search for Freedom and Prosperity in the Koyukuk Gold Fields of Alaska” (2019) written by Margaret Merritt, PhD. I reject the assertion put forth in the aforementioned work that Creecy was running away from racism and the systematic oppression of African Americans. Rather, I am curious to know what Creecy was running towards. In a conversation with my friend and culture bearer Diane “Bunny” Fleeks, a lifetime resident of Fairbanks, she similarly rejects the idea of the telling of Creecy’s story as a means of escape. She, like me, loves Alaska and thinks it is possible that Creecy came to Alaska in search of gold, but fell in love with this land and decided to stay; only leaving once for a lengthy hospital stay in Seattle in 1935 after he fell ill.

Film archivist Angela Schmidt, left, and author M.C. MoHagani Magnetek, right, in the film vault of the UAF library. Schmidt holds an original canister containing Harry Leonard’s film of Roshier Creecy. M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

I BEGAN MY QUEST to know more about Creecy by visiting the University of Alaska Fairbanks Elmer E. Rasmuson Library. Yes, going to the library is still high-tech cutting-edge anthropology, well at least I consider it so because the library has digitized film and audio recordings. Furthermore, I had so much fun spending an early summer day reading and scanning photos, letters, grocery receipts, and newspaper clippings recovered in Roshier Creecy’s cabin after his passing. UAF library film archivist, Angela Schmidt, led me down to the film vault to see the original film canisters of filmmaker and friend to Creecy, Harry Leonard, who filmed Creecy in the 1930’s/1940s. Because the film is so old, the archivist could not put it on the projector for me to see but we did watch the digital version. Thanks to Leonard, we have the only footage as well as still images clipped from the film of Creecy alive with his dogs, and sled, panning for gold in front of his Wiseman cabin.

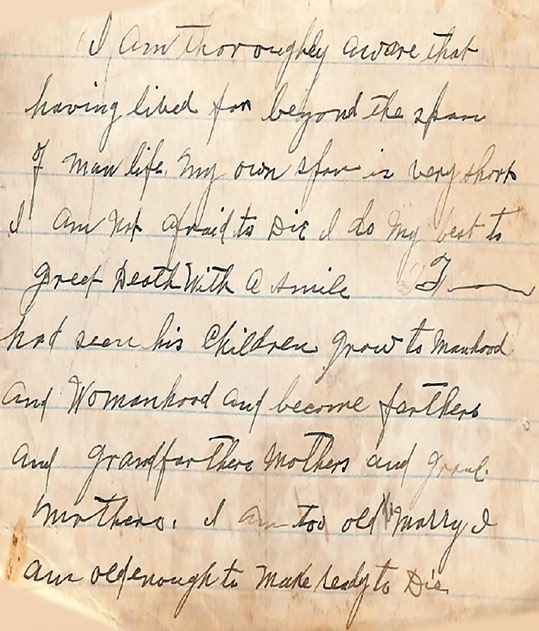

The UAF archive is filled with materials and primary documents, such as the scraps of paper, often undated and without context, on which Creecy used to jot down notes such as needed provisions, how cold it was outside, or his son’s name and moments of life reflections. On a scrap piece of paper recovered from his cabin, retrieved in the library’s Roshier Creecy collection, we get a sense of his mental wellbeing and attitudes towards aging and marriage via his own handwriting:

“I am thoroughly aware that having lived from beyond the span of maw life. My own span is very short. I ought not be afraid to die. I do my best to greet people with a smile. I … had seen his children grow to manhood and womanhood and become fathers and grandfathers. Their mothers and grandmothers. I am too old to marry and old enough to make ready to die.”

"They were here for a purpose. They weren’t running out of town... They were coming to a life that they thought that they could create for themselves that was much broader, much bigger."

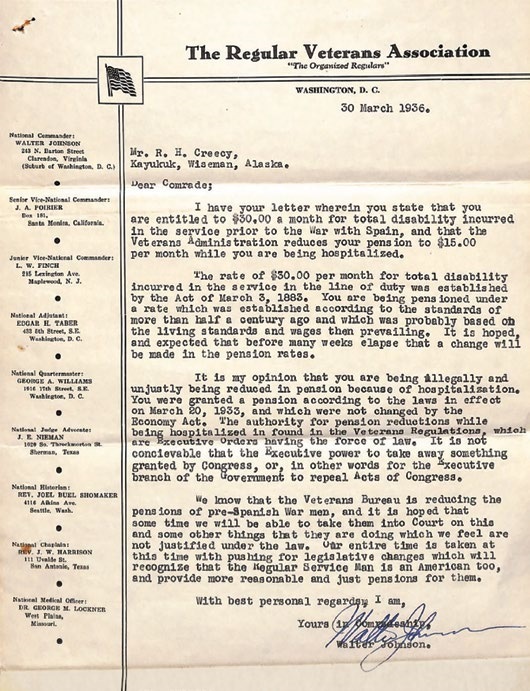

The moment my fingers parted the archival folders, and I came across a 1936 letter from a representative of The Regular Veterans Association addressed to Creecy, I knew I had to call and talk to my dad, Stacey Wilburn, Sr. I told my dad that I’m studying documents from another African-American veteran who lived over a hundred years ago and how Roshier Creecy remained in constant communication with the VA. I call my dad for anything VA-related because he is an Army vet and taught me, as he says, “how to handle my business” at the VA. My dad replied, “Ain’t nothing changed, it’s still the same. You got to read to have knowledge for yourself,” because the VA is accessible; you just have to follow through with all the paperwork. Several other letters in the collection highlight Creecy’s persistent communication with the VA.

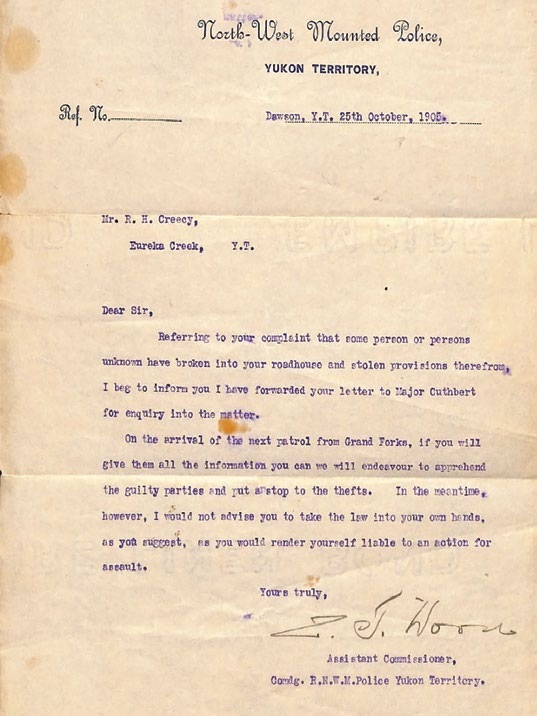

In 1905, Roshier Creecy wrote a complaint letter to the Canadian police to report the burglary of his Eureka Creek Roadhouse. I wish we had access to Creecy’s letter to the North-West Mounted Police because the Assistant Commissioner responded to Creecy’s upset tone about the break-in and theft of his provisions. After informing Creecy of the impending investigation the commissioner writes, “In the meantime, however, I would not advise you to take the law in your own hands, as you suggest, as you would render yourself liable to an action for assault.” I believe Creecy had a great deal of agency, meaning he did not allow anyone to cheat or shortchange him on his money, and he believed he must defend and protect his belongings even if it meant going above the law. However, this is only my interpretation and takeaways from reading the correspondence letters.

AFTER THOSE TWO DAYS in the library, I caught up with another friend of mine, archaeologist Steve Lanford, in the archaeological collections of the University of Alaska Fairbanks Museum of the North to tell him about my findings and to ask him a few questions about Creecy and Klondike Gold Rush history. He told me that if I was snooping around the archive collections in the library then I was in the right place because that is where the bulk of all that is known about Creecy resides. I felt rather good about myself with the affirmation that I was on the right path. I must be honest, I do ethnographic research because I love sitting with the Elders and listening to their stories, tall tales, and wisdom.

Correspondence between Creecy, The Regular Veterans Association, and the North-West Mounted Police. M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

Correspondence between Creecy, The Regular Veterans Association, and the North-West Mounted Police. M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

Fragment of Creecy’s writing recovered from his cabin after his death: “...I ought not be afraid to die. I do my best to greet people with a smile....” M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

My library adventures continued on to access the audio files housed in the library archives. There are nine audio recordings available; however, for brevity I choose an October 9, 1978, interview with Creecy’s son Nathan Cristini, recorded by documentarian Joseph Strunka. In 1917, Nathan met his father for the first time in Bettles, Alaska, and spent one year with his father as a placer miner. Nathan spoke about his dad’s affinity for apricots, reading, and sense of humor. Nathan recalled his father’s pranks in which he pointed a miner in the wrong direction. Sometimes he used the n-word to refer to himself as someone with ingenuity, charisma, and trickster-like tendencies. Such audio recordings enhance our research with rich, juicy, and savory anecdotes about Roshier Creecy that afford us in the present the opportunity to know who Roshier Creecy was as an individual beyond placer mining or being African American for that matter.

Archived collections and old audio-recorded interviews did not satiate my appetite for writing a complete story. I needed more ethnographic information, so I arranged a meeting with my friend, the theatre director, historian, and culture bearer Diane “Bunny” Fleeks on a Friday evening at The Boatel Bar in Fairbanks. Sitting there on the outside deck sipping on a Lemon Drop mixed drink located on an oxbow bend of the Chena River, I listened and used my iPhone voice recording app to chronicle our conversation. We spoke about many different matters as they related to the history of Black folks in Alaska. My mind was blown away by the amount of knowledge and depth of historical knowledge about African Americans in Fairbanks and Alaska as a whole.

On the topic of Roshier Creecy’s presence as the only African American in Wiseman for thirty years, Diane said the stories, “...tend to get told in a way that we’re this kind of special, special, special flowers, but are we? I don’t think of myself as anything but I’m pioneering things and I’m over 60.” Regarding Creecy’s motivations, Diane agreed with me that Black folks who travel, move, and choose to stay in Alaska are not necessarily running away from troubled circumstances; rather, “...they were here for a purpose. They weren’t running out of town. You know or anything like that. They were coming to a life that they thought that they could create for themselves that was much broader, much bigger... so when we are talking about our motivations, we always have to ask, ‘What are we doing?’”

I know this is true in my own expedition to establish a life for myself here in Alaska. I had the choice of leaving New York City when I was medically retired and discharged from the Coast Guard in 2012 to relocate back to Houston, Texas (my birthplace), Atlanta (where my immediate family resides), or go back to Alaska after having been gone nearly twenty years since I graduated from East Anchorage High School in 1994. I won’t lie, I was somewhat afraid to move so far away from all my blood relatives, but I sought adventure and a place to heal from the trauma I experienced on active duty. My dad, who is a great source of information and support to me, told me to not have any fear and to go live wherever I want to live and be whoever I want to be. Yet, these anecdotes about our lives and that of Roshier Creecy are insider information, also known in anthropology as emic distinctions, as opposed to etic distinctions (outsider point of view) that often result in assumptions that may or may not be true. Creecy left behind a few notes here and there but no detailed diary of his feelings, emotions, and adventures. The closest we can get to understanding Creecy’s personhood are the stories that were told by the people who knew him well and even to a degree those are assumptions at best.

To Alaska out of fear or to Alaska towards self. I’m looking at rather moving towards an anthropology of self in which the individual and personhood take centerstage beyond culture and society. Us diasporic Africans who call Alaska home often hear from others when we tell them we live in Alaska, “Oh, there are Black people in Alaska?” and then they may ask how we fit in or relate to Black culture. But I ask what difference does it make when people akin to Creecy, Fleeks and I are more interested in being ourselves rather than proclaiming or defending our claims to African cultural identities?

Roshier Creecy’s school portrait. M.C. MoHagani Magnetek

No doubt racism, bigotry, and discrimination of yesteryear and today give pause to run off into the Alaska wilderness without looking back. However, we engage in our own sense of self as we trailblaze and cut down new paths in the Alaska terrain for those who choose to follow us. Our identities are not derived from our cultures or circumstances for that matter rather originate from ourselves. What is self? I’m not talking about one’s identity. I do not just identify as an African. I identify as queer, as a poet, as an archaeologist, a mother, and a wife… these intersectional pluralities of mine with the understanding of “self” at the center. I treat this self as a reflexive state of being in which I transit the terrain aware of my actions and inactions; my attitudes and my thoughts regarding my own survival.

Now that I think about it casually, Roshier was on his own path and loved it. He could have taken his money back to the Lower 48 and lived a plush life of riches but he did not. According to the oral narratives recorded in the Strunka interviews of Creecy’s family and friends, Creecy often sent money and gold nuggets to his family in Virginia. He had income through his placer claims, gemstones, and gold findings. On top of all that he had a $30 monthly pension from the VA, which is a substantial amount of income in 1948. He could have made it anywhere he traveled but he chose to remain in Wiseman, Alaska until he froze to death in the winter of 1948 with his arm stretched out as if he was reaching or stoking a fire while lying down. The oral accounts state in order to fit him in his casket they sawed off his arm. I imagine to this day he is still cracking jokes from the great beyond with one arm eating apricots, reading Negro Digest, and hanging out with his dogs.

This entire research and writing is a work in progress. I am just now beginning to venture deep into the fireweeds of individual anthropology, material culture collection, and ethnographic analysis of people like Roshier Creecy here at the base of my climb, running towards an anthropology that investigates individuals who look like me in the Circumpolar Far North. For now, I am enjoying this moment of anthropological exploration and reflection. ■

M.C. MoHagani Magnetek holds degrees in anthropology and English, and has an MFA in creative writing and literary arts. She is a PhD student in cultural anthropology and historical archaeology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. She is currently working on getting her life together to focus her doctoral studies on the culture, history, and arts of diasporic African people in the Circumpolar Far North. Frying fish is her favorite pastime.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

November 13, 2025 • MoHagani Magnetek & Polly Carr

November 12, 2025 • Becky Strub

November 10, 2025 • Jim LaBelle, Sr. & Amanda Dale