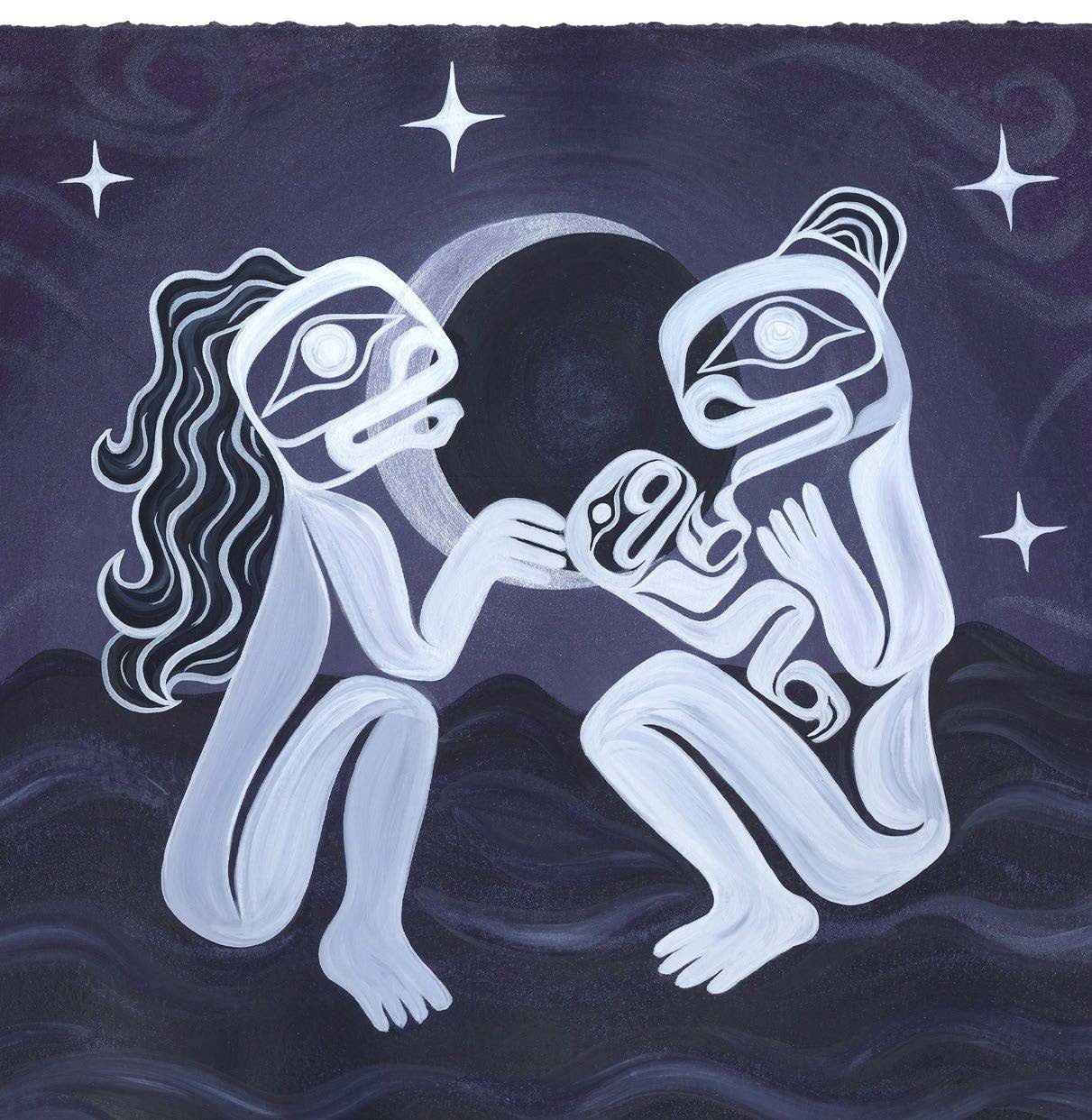

Crystal Worl, “Storytime at Moonrise,” 2019, gouache paint.

Crystal Worl, “Storytime at Moonrise,” 2019, gouache paint.

by E.J. David Ramos

Winter 2022-23, FORUM Magazine

“Filibascan” is what I call my Filipino-Athabascan kids. I believe the term captures their roots and our multiracial family quite well, but also pays homage to the many mixed-race Alaska Native-Filipino people who have historically referred to themselves as “Indipinos,” “Tlingipinos,” “Eskipinos,” or other similar derivatives. I’ve used the term Filibascan so much over the years on social media, in my writings, speaking gigs, and media interviews that it became—surprisingly—a central storyline in a “Molly of Denali” episode!

“Wait, there are Filipinos in Alaska?!?”

This is a statement—both an expression of shock and a question—that people often make when they find out that I’m Filipino, that I focus my research on Filipino Americans, and that I live in Alaska. Since the “Molly of Denali” episode aired, I’ve been faced with this question even more.

Americans generally don’t know much about Filipinos, and even those who have some knowledge probably think of other states like California or Hawaii as the Filipino American hubs… not Alaska. And though there is truth to this dominant narrative—as census data shows that approximately 35% of Filipino Americans live in California and Hawaii alone—Alaska should also be part of the Filipino American hub category. This is because Asians make up around 8.4% of Alaska’s population—higher than the national rate of 7.2%—and approximately half of this large Asian community is Filipino. It goes against most people’s mental schemas when they find out that Filipinos form the largest Asian group in Alaska. People are even more surprised when I tell them that most immigrants in Alaska are Filipinos rather than Mexicans or members of another Latin American community.

Crystal Worl, “Goodnight, Baby,” 2019, gouache paint

Aunties and Art

CRYSTAL WORL, whose paintings appear above, has Tlingit, Athabascan, and Filipino ancestors. She was raised in a traditional Indigenous family with close ties to its extended kin. “I was raised by my parents, grandparents, uncles, and aunties,” she says. “My mom’s family is the largest in the state. I meet new cousins, uncles, and aunties all the time.”

From Crystal’s perspective, being a family means sharing values and time. “We cook together; we clean together; we talk and laugh together. If I am doing art and there are little kids, sometimes I’ll be doing art with them or playing with them. Sometimes we’ll watch movies together. If I have something going on for my art, I invite my family because it’s always better to have them there.”

Her art often features family activities, depicting “a lifestyle in Alaska, being out in the land, fishing and hunting with aunties and uncles, or picking berries with mom or stepmom. Those are things we do with the family, things we do to feed ourselves and to be healthy and active. Our families have done this for many generations, for ten thousand years.”

It astounds people even more when they learn that it was way back in 1788 when the first Filipino set foot on what is now known as Alaska and that larger waves of Filipinos came to the state in the early 1900s.

“Ok, that’s cool… So, what’s it like to be a Filipino Athabascan family?”

Since the “Molly of Denali” episode, this has also become a frequently asked question. I’m not Athabascan, so I’m not the best person to speak to that part. But I believe there are similarities between the Filipino and Athabascan experiences, so I’ll share a bit about the Filipino part. Perhaps that can provide some hints about the Athabascan side as well.

Being Filipino, for me, entails many complexities. One commonly debated issue is where we fit in this country’s categorizations of race. I remember being confused with this as a 14-year-old immigrant when I had to check a race box for the first time on a form I was filling out for school. I considered checking the “Asian” box because the Philippines are geographically part of Southeast Asia. But I also felt like checking the “Latino” box because of our colonial history and many cultural and religious connections. Then I saw “Pacific Islanders” and thought, “Well, the Philippines is a country of over 7,000 islands in the Pacific Ocean, so…” I also saw “Caucasian” and thought, “I’m not sure what ‘Caucasian’ is, but could it mean ‘kinda Asian’? Is that what I am?”

Eventually, I asked an adult to help me, and they said, “Check ‘Asian.’” So I did, but I felt weak afterward for acquiescing to something that didn’t feel completely right.

JUST RECENTLY, I feared that I’d passed this weakness on to my kids when my 9-year-old son shared with me an interaction he had with a classmate of his, who is also Filipino. “Dad, my friend said if you’re Filipino, you’re Asian. Is that true?” he asked me. I replied, “That’s what many people think.” He followed up with “So I’m Asian?” seemingly with the same resignation I felt when I was told to check the “Asian” box almost 30 years ago. I was concerned that my son had relented as I had, so I asked him how he felt about that. He said, “I dunno. But I told my friend he can’t tell me what I am. I’m Filipino, not Asian.”

I guess I was wrong. My son didn’t feel forced to adopt a label that seemed ill-fitted for him. He went against the dominant narrative. He refused to be racialized.

It astounds people even more when they learn that it was way back in 1788 when the first Filipino set foot on what is now known as Alaska.

I’m proud of my son, and yet the fact remains that this country forces us into a category many of us feel we don’t belong in; this is further complicated by the fact that being generically classified as “Asians” makes us even more invisible. When many people think of Asians, the image that pops into their minds is more likely to be of someone whose heritage is Chinese, Korean, or Japanese than Filipino. Nonetheless, Filipinos compose approximately 20% of the Asian American population, and Luzones Indios from the archipelago were the first Far Easterners to set foot in what is now the U.S., in Morro Bay, California, way back in 1587.

This is why Filipino American historian Fred Cordova regarded Filipinos as “the forgotten Asian Americans.” Despite our large numbers and long history in this country, we continue to be invisible. Sure, we are strong and resilient. Surviving over 400 years of colonialism that systematically subdued our cultures and bodies attests to this. Another example is our ability to relate to and even blend with various cultural groups. We can even accept being forced into a racial category with people to which we don’t feel completely connected. But it seems that our ability to adapt, tolerate, and even assimilate has been employed as a means to perpetually ignore, disregard, and erase us.

Our resilience has been used as permission to condone our continued oppression.

THESE ARE the main reasons why it’s often hard to find something to be proud of as a Filipino, especially in the U.S. This invisibility and continued oppression prime us to accept whatever people tell us we are and what we should be. So, what we often end up taking pride in is our ability to adapt and change ourselves, not realizing how this potentially contributes to how much we forget ourselves. This may be why confusion about our identity and self-hate are so common among us. And although my research over the past two decades supports this, it’s my own personal struggle in this country that makes me know this.

There was a time when I was ashamed of my roots, when I believed being able to speak English well was a sign of intelligence and sophistication. It was a time when I equated lighter skin tone with beauty while associating darker skin and rural, non-Western origins with inferiority. It was a time when I regarded anything “Made in the U.S.”—and anything about the U.S.—as better than anything by, from, and of the Philippines. My colonial mentality was deep and automatic.

My son flipping the script from cultural shame to cultural pride—from my perceived inferiority to him seeing his roots as sources of strength—is an embodiment of intergenerational healing in real time.

And I fear that I might pass on this colonial mentality to my kids.

But I see my kids resisting. My 9-year-old son, for example, has repeatedly chosen to wear a Barong Tagalog—a traditional formal long-sleeve shirt—for school picture days. I didn’t have the courage to wear one in the American school system when I was younger, so to see my son proudly and automatically representing his Filipino self makes me so happy. I love that it’s just normal for him to be proud of his roots: no second thoughts, no shame, no doubts.

People talk about intergenerational trauma in our communities, and that’s important, but we must not fail to see that intergenerational healing is also happening. My son flipping the script from cultural shame to cultural pride—from my perceived inferiority to him seeing his roots as sources of strength—is an embodiment of intergenerational healing in real time.

MY IMPRESSION is that my kids will feel similar struggles and tensions through their Athabascan roots. There are fears about intergenerational trauma and questions about belonging and racialization in that community, too; there are also issues surrounding blood quantum, authenticity, and other racial and cultural identity traits. Perhaps the clearest symbols of this are the ID cards telling my kids that they’re only part Athabascan. My wife and I tell our kids to ignore that. Instead, we teach them to see themselves as 100% Filipino and 100% Athabascan. It doesn’t make sense to us that 100% me plus 100% my wife equals anything less than 200%. Racism has become so insidious that it got us distorting basic math.

Our kids know they’re 200%. And if people question them, arguing that 200% doesn’t make sense, that’s okay. Our kids know that their roots are their superpowers and that, for most people, superpowers don’t make sense.

I guess this is what it’s like to be a Filibascan family. We face plenty of struggles and confusion and must constantly resist societal impositions and oppression. But there’s also plenty of healing and continually reminding ourselves that our struggles and confusion are not because of who we are, but due to dominant and yet limited societal conceptualizations of who we are.

We rise above and beyond these limitations. Our superpowers allow us to do so. ■

E. J. R. David, Ph.D. is a professor of psychology at the University of Alaska Anchorage, specializing in ethnic minority psychology. He has written Internalized Oppression: The Psychology of Marginalized Groups; Brown Skin, White Minds: Filipino-/American Postcolonial Psychology; The Psychology of Oppression; and We Have Not Stopped Trembling Yet. Among numerous professional honors is his induction as a Fellow by the Asian American Psychological Association for “unusual and outstanding contributions to Asian American psychology.”

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

January 20, 2026 • Shoshi Bieler

November 13, 2025 • MoHagani Magnetek & Polly Carr

November 12, 2025 • Becky Strub