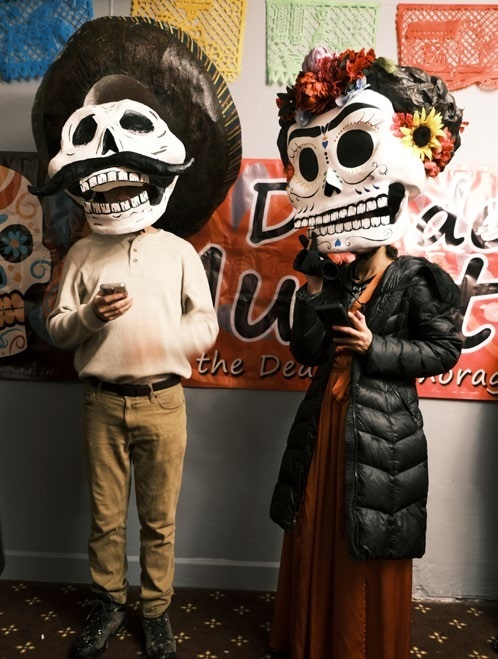

2022 Day of the Dead Celebration, Anchorage. Mexicans place photographs, candles, flowers, food, candy, and paper decorations in the ofrendas to please their ancestors who come to visit. Dan Bailey

2022 Day of the Dead Celebration, Anchorage. Mexicans place photographs, candles, flowers, food, candy, and paper decorations in the ofrendas to please their ancestors who come to visit. Dan Bailey

by Gabriela Olmos

Winter 2022-23, FORUM Magazine

NOVEMBER 2, 2018, was a special day for Anchorage’s Mexican community. For months, a handful of its members had prepared for the Day of the Dead festival. They met weekly in the studio of artist and community leader Indra Arriaga to make paper flowers, cutouts, and—by the most skilled members—giant papier-mâché skulls.

When the expected moment arrived, people gathered in front of the Anchorage Museum. Itzel Zagal, an Aztec dancer of the Nahua tribe, opened the event with a blessing. Dressed in a traditional costume, she greeted the cardinal points with the popox-comitl, or incense burner, as her ancestors did.

In freezing weather and with over 10 inches of snow on the ground, dozens of people walked in procession to follow Death herself, who was dressed in the style of a nineteenth-century lady. Her head was one of the enormous sculptures that the artist Macuca Cuca built at the community gatherings. Death traditionally wore an elegant, wide-brimmed hat.

Who said that Death must always be a woman? Alongside her walked Mr. Death, a skull-headed gentleman dressed in the nineteenth-century style and with a top hat. Behind them, men, women, and children—some with their faces painted in the traditional skeleton style of the event—wandered the streets of the city center. Onlookers joined the festive procession in awe. After all, it’s not every day that one has the honor of having fun with the dead.

The 2022 celebration took place downtown. Itzel Zagal led the Aztec dancers. She opened the ceremony by greeting the four cardinal points. The butterfly on her dress is an important symbol of the Aztec culture. Dan Bailey

By the time the procession arrived at the gallery that hosted the event, over a hundred people were following Death. The community received the parade with steaming cups of hot chocolate and pan de muerto, sweet bread made especially for the celebration.

After warming up their bodies, attendees visited the altars. Half a dozen families and students from the Government Hill Spanish Immersion Program set out these ofrendas, which included portraits of their ancestors, paper flowers, candles, chocolate or sugar skulls, bread, food, or tequila. The ancestors must have been pleased with the colorful display. After all, they had returned from the underworld ready to party!

A face painting booth was busy in a crowded corner of the party. All in attendance were allowed to decorate their faces, but women and children monopolized the line. They all chose to look like skeletons, perhaps in a desire to intermingle with the ancestors.

Dance troupes added a colorful note to the party. The ancestors must have loved the dresses that swayed to the rhythm of Mexican folk music. The local mariachi band played the final songs while Mexicans sang and hugged each other, sure their ancestors were singing along.

When most attendees left the gallery, the organizers toasted with hot cocoa, “Cheers to the joy of becoming a chosen family!”

With the altars right there, the conversation easily falls into evocations of the ancestors: “Do you remember when he did this or that?”

Mexicans boast of laughing at death. Laughing at death is an essential part of their culture.

Pre-Hispanic peoples living in the land that today is Mexico did not consider life and death as absolute opposites but rather as points on a continuum. The idea of individualism arose with colonization. According to Nobel laureate Octavio Paz, the current vision of death in Mexico emerged from the encounter between these perspectives.

Death makes us all the same. The oppressor and the oppressed, the rich and the poor—all will turn to bones and dust. The rich may fear their empires will collapse, but Mexicans believe they have nothing to lose. And so, they laugh.

The idea of sinister skulls as part of the Day of the Dead came about in the nineteenth century. They became a popular element of the celebration in urban areas. However, people in rural Mexico celebrate in a different way. They believe that ancestors come to visit their kin on those days.

While researching the topic between 2000 and 2003 for the arts publication Artes de México, I witnessed some elements that Mexico’s rural communities include in their celebrations. Church bells toll on the eve of the festival, opening the door that divides the underworld from the human world. The ancestors will be able to cross the “bridge” once this door is open.

On November 1, those who died as children—the so-called “little angels”—visit their living relatives, who have placed offerings of toys to receive them. Adults who have passed away make the journey on November 2. Instead of toys, they might be offered their favorite food and tequila.

Attendees paint their faces as skeletons. For Mexicans, face painting is not a costume but a ritual element full of symbolism. Dan Bailey

People often make a narrow path of marigold flowers from the street to the ofrendas. They say that the ancestors see the flowers as candles lighting their way to the altars. However, ofrendas may also have candles.

Cooks often prepare celebratory food, including tamales. They serve a portion in the ofrenda for the ancestors to enjoy during the feast. I once asked how we know the ancestors ate the food if we keep seeing the dishes untouched. People explained that the ancestors eat the aroma of food. Because the ancestors have no bodily substance, they do not need the actual physical food, only its “spirit.”

Altars can also include drinks for the ancestors, such as hot chocolate, coffee, and any alcoholic beverages they like, as well as objects that trigger memories of the deceased, including pictures, personal belongings, and games. Finally, ofrendas include salt and water used to purify the space, as those liminal moments when the door to the underworld is open could be dangerous.

Different members of the Mexican community have been involved in organizing the Day of the Dead celebration since its creation more than fifteen years ago. Dan Bailey

During the Day of the Dead, the acts of the living mirror those of the ancestors. So, while the dead visit their offerings, members of the community visit each other. Each time someone comes to a home, the hosts will offer mole, tamales, hot chocolate, pan de muerto, and whatever dishes they have prepared for the ofrenda.

With the altars right there, the conversation easily falls into evocations of the ancestors: “Do you remember when he did this or that?” “Don’t you like how he solved this or that problem?” Time flies when remembering loved ones. The community builds new memories while sharing those that remind them of the deceased. Children are often there, connecting with each other while learning about their kin.

Food and memories from the Day of the Dead are gifts that call for reciprocity. The exchange is not just for more food and more memories in future celebrations. With ancestors as witnesses, community members sign a silent contract, guaranteeing each other a network of support. This concept of exchange and support is called guelaguetza. With the help of the vertical relationship of the ancestors, Mexican communities establish a horizontal web of relatedness.

Community members sculpt paper-mâché skulls throughout the year to celebrate their ancestors in November. Dan Bailey

The Day of the Dead in Anchorage, Alaska, has some peculiarities. Nostalgic for their homeland, Anchorage’s Mexican immigrants see in the festival the possibility of reconnecting with their culture. They all come from different parts of Mexico—from the big cities, including the 20-million-person capital, to the small, Indigenous towns of rural Mexico. They bring to the celebration whatever they experienced back home. Alaska’s particular landscape and the mix of elements from urban settings with those of rural areas makes Anchorage’s Day of the Dead unique.

While working together, Mexican immigrants build their chosen kinship bonds during the festival. Hard work and reliability will help if, say, someone falls into the ditch while driving or needs to go to the hospital at night during the year ahead. They build relationships, choosing a “family” that could help them survive in this cold paradise.

Mexicans like to seal this collaboration pact during the Day of the Dead. They work, eat, drink, tell stories, dance, and sing. The ancestors will witness the reciprocity agreement, smile, and give their descendants their blessing. Proud of their kin, they will walk back home with cold feet but warm hearts. The ancestors’ spirits are light, and they do not leave footprints in the snow, but Mexicans’ hearts swell with joy, memories, and connectedness—the unmistakable mark of the ancestors’ presence. ■

Gabriela Olmos has written fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Her articles, short stories, and poems have appeared in periodicals in Latin America, Europe, and the U.S. She has published 16 children’s books. Eight of them are part of public education programs in Mexico. She received an International Latino Book Award in 2019. She has worked as an editor for more than 20 years.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

April 16, 2025 • Kameron Perez-Verdia

March 5, 2025 • Polly Carr

February 25, 2025 • Amanda Dale