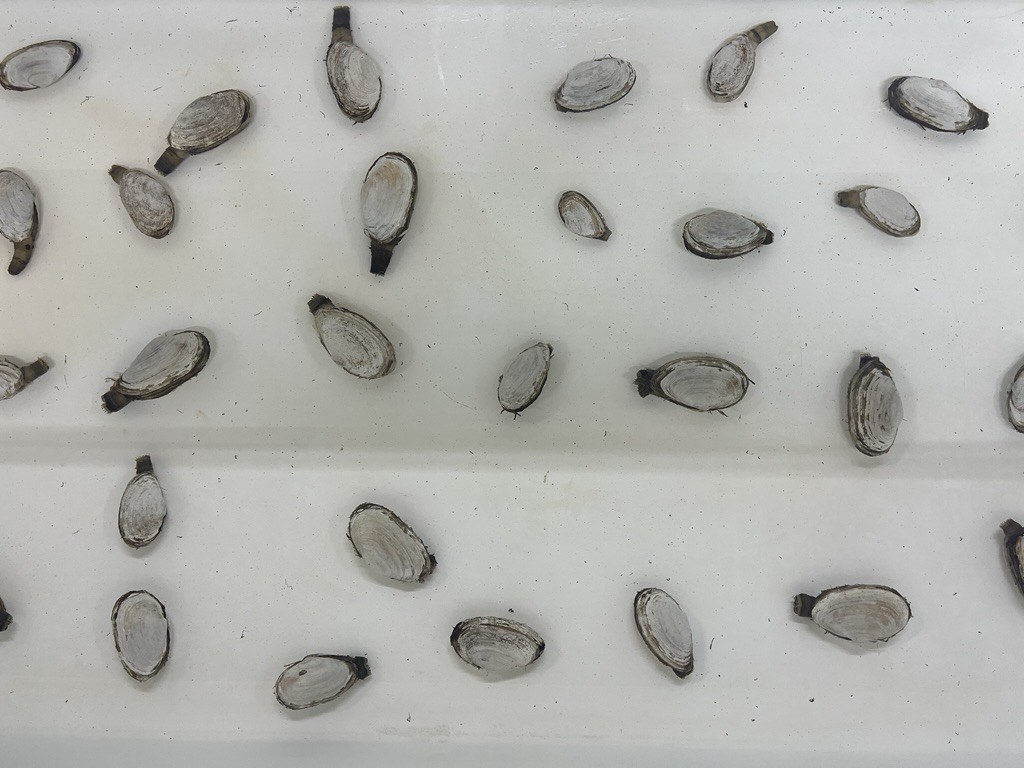

Clam spawning season at Alutiiq Pride in Summer 2024. Credit: Robin McKnight.

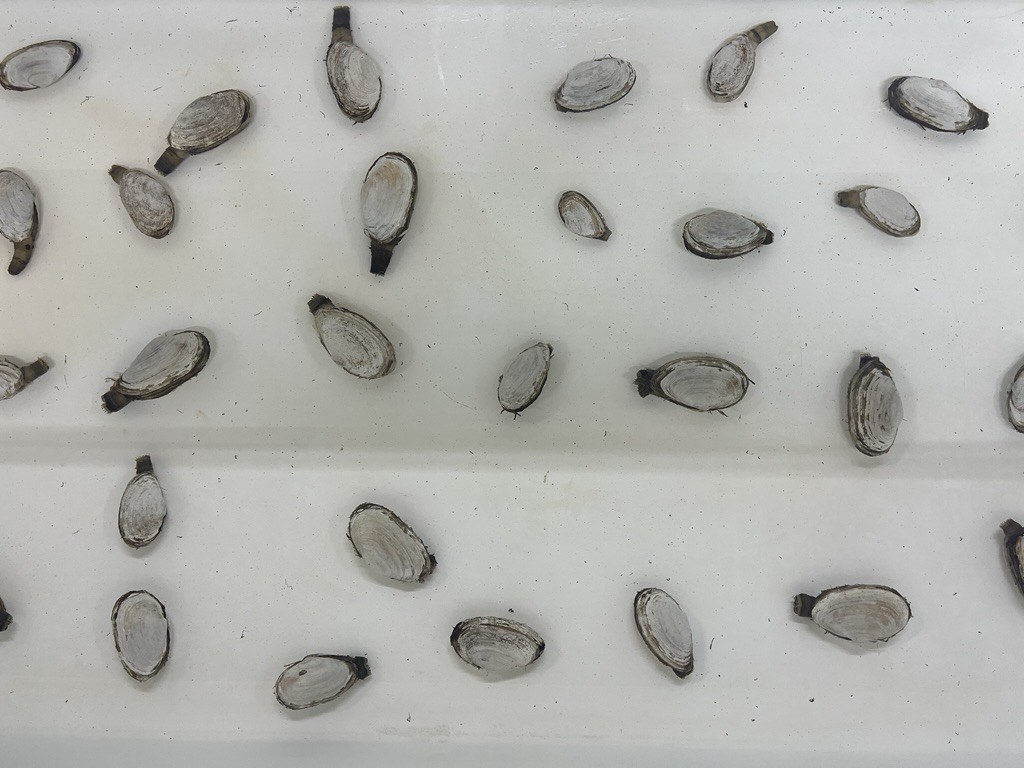

Clam spawning season at Alutiiq Pride in Summer 2024. Credit: Robin McKnight.

By Robin McKnight

Winter 2024-25, FORUM Magazine

IF YOU STAND IN THE CENTER of the main building bay at Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute in Seward and close your eyes, it feels as if you are submerged in a tide pool.

Whirring sounds emit from the pipes and water intake, the filtration system, where thousands of gallons of seawater enter the building each day. Air bubbles into the massive tanks that line the majority of the room, as if you are next to a small underwater air vent, a diluted and ever-present noise. It’s warm, and there is an energy to the building that feels dynamic, as if, at any moment, the foundation itself could move. The smell of low tide permeates the humid air. Salt, grit, seaweed. You are only one of the thousands of living creatures here.

Even with wide-open eyes, Alutiiq Pride feels like stepping into a different world. That is unless you are an aquaculture technician or, perhaps, a clam. On my first morning in the shellfish hatchery and marine research facility on the edge of Resurrection Bay, I felt transported. Being from Seward, I was surprised I couldn’t find any memories of the internal building or the work taking place there beyond the people conducting it whom I knew from childhood. I still don’t know if, before a year ago, I had ever been inside.

That day, Alutiiq Pride was a mystery to me. It has been many things since its construction in the 1990s: an oyster hatchery, a classroom, a laboratory, a nursery for macroalgae, a gathering space, and a historical landmark. Most importantly, it is part of a larger story, and today, that story starts in the sand.

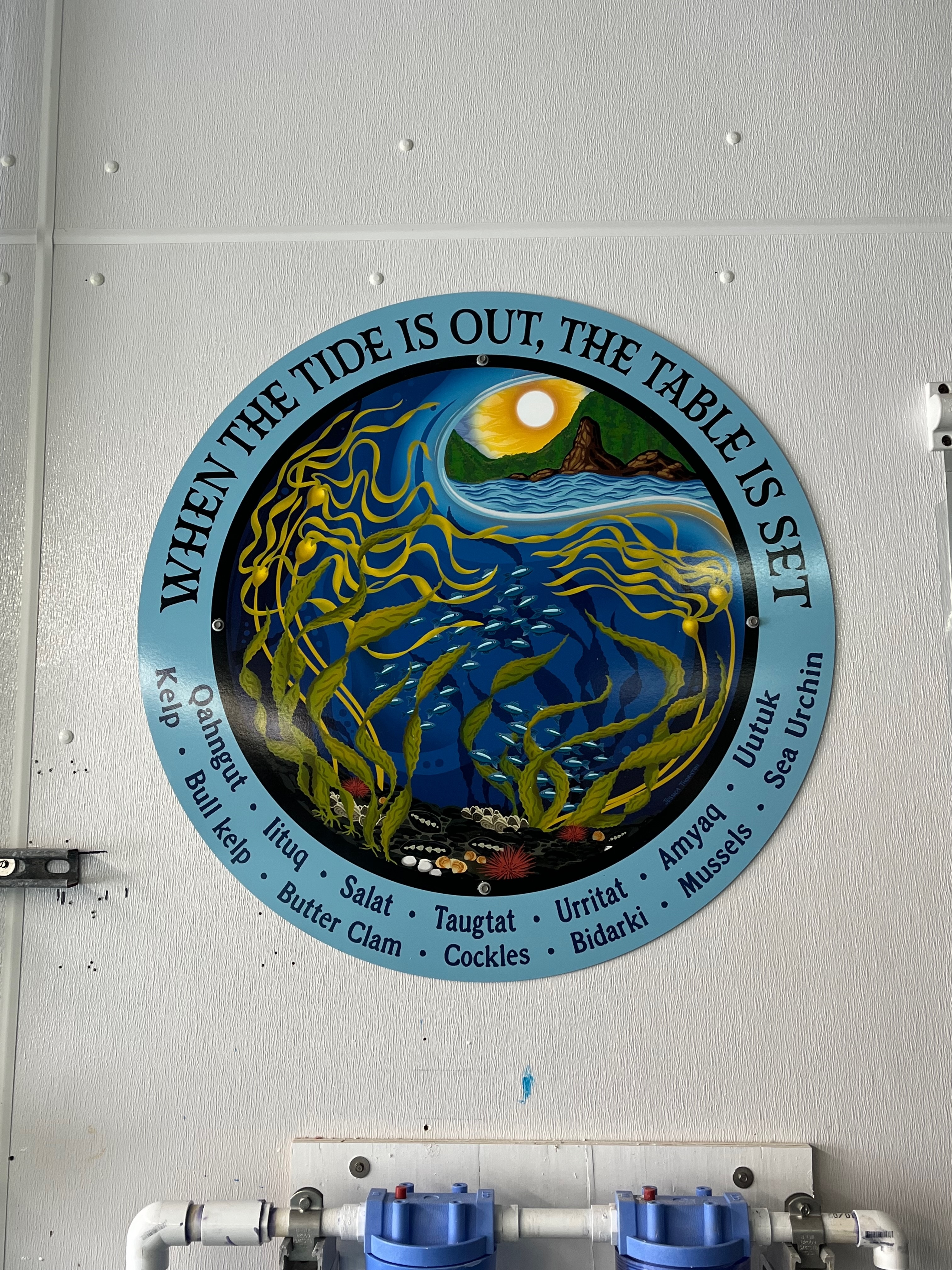

When the Tide is Out the Table is Set, on the wall of Alutiiq Pride's facility in Seward. Credit: Robin McKnight

---

Beneath the mucky alluvial fan that spans the head of Resurrection Bay rests a cockle. The serrated edges of its shell are clamped tightly together, protecting the soft muscle of the foot, the siphon used for filter feeding, and the reproductive organs. Using its foot for locomotion, the cockle moved through layers of sand and silt to rest at the interface between land and sea. From the surface, the beach appears flat, save the almost imperceivable bubbles rising from the still-wet black sand, reflecting the sky like glass. From above, the cool metal spade of a shovel strikes like a meteor, displacing sand. Footsteps vibrate, and a gloved hand reaches into the boundary between sky and sea, plucking the cockle from its home in the silt. It is deposited into a five-gallon bucket with a handful of other bivalves. It will not return to this beach but its offspring will.

Digging for clams is a dirty job and it happens every year at Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute, often referred to as APMI or “the hatchery” by employees. Not long after my first visit to APMI, I sat in the large office with Annette Jarosz, a shellfish biologist and the facility’s Mariculture Director, as she described clam surveys. The organized assessment of shellfish communities in a certain area is based on following transects along the beach. When these occur in early summer, broodstock and parent individuals are collected and brought back to Alutiiq Pride.

Like the cockle from Resurrection Bay, broodstock is collected from beaches and intertidal areas around southcentral Alaska where Alutiiq Pride’s parent organization, the Chugach Regional Resources Commission (CRRC), a non-profit Tribal consortium, serves the Tribal communities of the Chugach region. The work of CRRC spans as far east as Prince William Sound to Chenega, Tatitlek, Valdez, and Eyak in Cordova and also takes place along the Qutekcak Native Tribe’s Traditional lands in Seward and the Lower Cook Inlet villages of Port Graham and Nanwalek.

Arriving in a five-gallon bucket or cooler, by way of boat, plane, or car, the real journey for broodstock begins at the Alutiiq Pride hatchery. The nexus of this work happens at the center of the building. Taking up most of this main space is a series of tanks, waist high, filled with filtered saltwater. Bisected by circular dividers, these tanks house, at times, up to ten different species of shellfish and intertidal organisms at various life stages, according to Jarosz.

These stressors are as interconnected as the places they impact. The health of our diverse coastal and marine ecosystems depends on relationships between the biotic and abiotic, the checks and balances between two, three, and one hundred components of an entire dynamic, living system, including humans.

In the early 2000s, CRRC took over operations of the Alutiiq Pride facility from the Qutekcak Native Tribe and has been cultivating shellfish husbandry techniques and protocols since converting the Tribe’s oyster hatchery into a more diverse operation. As it is now, Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute is a cutting-edge research facility, mariculture technical center, and one-of-a-kind shellfish hatchery. The technicians and researchers who work with the shellfish are aquaculture experts. Parent shellfish are well fed by algae grown in-house and their tanks are regularly monitored for contaminants. During spring and early summer, APMI’s technicians encourage the broodstock to spawn.

As Jarosz explained to a tour group visiting the hatchery, this process simulates the natural environmental changes that would cue a spawning event. Jarosz and her team adjust temperature and light levels in the hatchery to replicate the natural environment’s spawning induction triggers. As spawning takes place in a dynamic environment (seawater), monitoring these events can often mean long hours of observation for the hatchery researchers. Spawning occurs once in the early summer when the populations of shellfish reach the hundreds of thousands in the hatchery. Shellfish larvae develop into juveniles over the winter under the dutiful eye of technicians. Once they are large enough (around a year old, depending on the species), the juvenile shellfish are returned to the beaches their predecessors were once collected from, restoring populations along the coastline of the Chugach region. The process begins again. Broodstock collection, population surveys, spawning, rearing, outplanting, rinse, repeat. It’s a lot of work but this is not work that happens without reason.

As the Education & Outreach Director of the Chugach Regional Resources Commission, Carol Conant likes to point out that Alutiiq Pride doesn’t do science just for the sake of science. APMI’s research is done on behalf of the seven Tribes of the Chugach region. The mission of CRRC is to support Tribal natural resource management, promote Tribal sovereignty, and protect the Traditional way of life across the region. On tours of Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute, Conant will often open her arms wide, as if to demonstrate the breadth of this work and say, “Everything we do comes down to people’s food”.

Shellfish are a vital subsistence resource in Southcentral Alaska, as well as in many other locations in the state. These are important Traditional food sources for the Suqpiat and dAXunhyuu (Eyak) and are an essential part of the diet of people across the Chugach region. Razor clams, basket cockles, littleneck clams, bidarki (black chiton), butter clams, soft shell clams. These species are part of an enduring practice, a relationship with harvesting food from the land and sea; they are integral to Sugpiaq and Eyak culture. Tamatum tuknigkuart’slaraakut. This is what sustains us.

Broodstock collection, population surveys, spawning, rearing, outplanting, rinse, repeat. It’s a lot of work but this is not work that happens without reason.

Many of these species are also weathervanes for environmental change. Bivalve and mollusk species are sensitive to shifts in the balance of their intertidal and beach habitats. As filter feeders, bivalves such as clams and mussels uptake and cycle plankton, algae, and nutrients directly from seawater. Many shellfish are keystone species; changes in their populations indicate changes in the surrounding ecosystem from various sources and stressors. Understanding the dynamics of these important subsistence species populations is vital for food security, harvest decision-making, and community well-being in the Chugach.1 And, reciprocally, generations of observation from Tribal members in the region provide the knowledge to accurately formulate and address research questions regarding these key species. Alutiiq Pride researchers must learn from the well of information that culture-bearers and knowledge-holders in the region have to offer. It is at the core of how the Chugach Regional Resources Commission operates. All science conducted is Indigenous-led and informed by the interests and questions of Chugach Tribal communities.

Concerns about the decline in shellfish populations have been present in the region for decades and have been of special concern since the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill.2 3 Despite the dependence on shellfish harvest by Tribal communities in the spill region, studies focused on Alaska Native subsistence shellfish restoration (co-conducted by CRRC) were not funded by the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council past the year 2000.4 Still, Tribal members and Elders continued to notice the loss of key subsistence species including cockles, butter clams, bidarkis, and razor clams, which have seen a near-total collapse.5 6 7

There are many historical and contemporary reasons for shellfish decline. Slow recovery from the oil spill region-wide, changes to ocean chemistry, over-harvest and exploitation, warming water temperatures, and increased predation by sea otters.8 9 10 These stressors are as interconnected as the places they impact. The health of our diverse coastal and marine ecosystems depends on relationships between the biotic and abiotic, the checks and balances between two, three, and one hundred components of an entire dynamic, living system, including humans. The causes for the decline are webbed through the sand, through the evergreen spruce boughs, through the ocean currents, and through time. Through the very people who live and depend on the health of these coastal lands and waters.

It is difficult to tease apart the existing knots between causation and outcome but this is part of the job at Alutiiq Pride. Be it changes to community dynamics, commercial exploitation, shifts in the food web, or climate change, understanding underlying stressors to shellfish populations and habitat is critical to restoring populations. Understanding the past is critical to the future. While APMI hatchery technicians collaborate with Chugach Tribes to restore shellfish across the region, the work doesn’t stop there.

Just as the cockle collected by one of APMI’s intrepid biologists is one part of a larger ecosystem to which it belongs, so is Alutiiq Pride’s shellfish restoration program to the Chugach Regional Resources Commission. Restoration cannot happen in isolation. APMI conducts habitat suitability studies, aids partners such as the University of Alaska Fairbanks with assessing how ocean acidification impacts shellfish,11 12 works with community members across the region to test seawater for harmful algae species, researches new husbandry techniques, and so much more.

The main building of the APMI facility houses laboratory space, tanks for shellfish, a nursery for kelp seed, ongoing and novel experiments, and a culture lab for algae. While they are not in the field or conducting research, the Alutiiq Pride team hosts tour groups, legislators, and regional partners. It is a space of co-creation, a place where Traditional Knowledge informs science. Here, you are just as likely to see a university researcher, donned in a white lab coat, as you are to see an intern in Xtratuffs, a tour group of elementary school students, or an Elder, leaning over one of the many tanks and pointing at a clam that will one day be buried beneath familiar sand.

Alutiiq Pride Director, Jeff Hetrick, and the late Chief Patrick Norman of Port Graham. Photo courtesy of the Chugach Regional Resources Commission.

---

Ken’aq qaillun stuuluq caskiumaqaq kentaqan cumi. When the tide is out the table is set.

My perspective has changed since my first visit to Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute. Now, when I walk through the rows of clam tanks, in between the glowing beakers of growing algae, by the researchers watching plankton on an illuminated microscope, I see a kitchen table. Now, when I close my eyes, I hear more than the whir of equipment, more than the gurgle of seawater, more than the splash of rubber boots against the shallow pools between tanks.

Let’s go back to where we started this. To the silty waters of Resurrection Bay, or Qutalleq, meaning “big beach” in Sugt’stun. The grit of sand, the slick of an unturned beach reflecting the sky in Nanwalek, or along the shores of Port Graham. The rocky tide pools of Chenega, the Copper River flats near Eyak, and the view of the sea from Tatitlek, from Valdez.

That single cockle collected from beneath the sand is not just one individual. It is the possibility of restoration. It is part of the ever-present, thriving connection the Alaska Native People of the region have to the land. It is culture, tradition, science, and stewardship. It is part future and part past, cupped in the palm of an outstretched hand.

---

Thank you to the Chugach Regional Resources Commission for your work & your mission.

Thank you to the Elders and Tribal members whom I am learning from all the time. Quyana for sharing.

To learn more about the Chugach Regional Resources Commission and its Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute, please visit: http://www.crrcalaska.org ■

Footnotes

1 Keating, J.K., G.P. Neufeld, A. Jarosz, and J. Hetrick. 2024. Clam Reintroduction in Chenega, Alaska: A Mixed-Methods Approach to Recovery. Alaska Department of Fish and game Division of Subsistence, Technical Paper No. 498, Anchorage.

2 Ibid

3 Brooks, Dr. K. M., Agosti, J., Hetrick, J., & Daisy, D. (2001). Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Restoration Project Final Report: Clam Restoration Project. Restoration Project 99 13 1 Final Report.

4 Ibid

5 Salomon, A. K., Tanape, N., Anahonak, P., & Huntington, H. P. (2011). Imam Cimiucia: Our Changing Sea. Alaska Sea Grant College Program.

6 Bishop, M. A., & Powers, S. (n.d.). Restoration of Razor Clam (Siliqua Patula) Populations in Southeastern Prince William Sound, Alaska: Integrating Science, Management, & Traditional Knowledge in the Development of a Restoration Strategy.

7 Olsen, L. (2015, March 5). Cause of razor clam decline remains mystery. Homer News. https://www.homernews.com/news...;

8 Dobbyn, P. (2018, October 4). Study explores decline of Cook Inlet razor clams. UAF news and information. https://www.uaf.edu/news/archi...’s,Department%20of%20Fish%20and%20Game.

9 Fukuyama, A. K., Shigenaka, G., & Coats, D. A. (2014). Status of intertidal infaunal communities following the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 84(1–2), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marp...;

10 Salomon, A. K., Tanape, N., Anahonak, P., & Huntington, H. P. (2011). Imam Cimiucia: Our Changing Sea. Alaska Sea Grant College Program.

11 Dobbyn, P. (2018, October 4). Study explores decline of Cook Inlet razor clams. UAF news and information. https://www.uaf.edu/news/archi...’s,Department%20of%20Fish%20and%20Game.

12 Washburn Alcantar, M. (2024). Characterizing Ocean Change Impacts on Three Marine Species Vital to Recreational, Subsistence, and Commercial Fisheries in Alaska (thesis).

Robin McKnight is an Education Specialist & Science Communicator, amateur birder, and poetry enthusiast. She is always down to go tidepooling. Robin is a 2024 FORUM Writing Fellow.

FORUM is a publication of the Alaska Humanities Forum. FORUM aims to increase public understanding of and participation in the humanities. The views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the editorial staff or the Alaska Humanities Forum.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

April 16, 2025 • Kameron Perez-Verdia

March 5, 2025 • Polly Carr

February 25, 2025 • Amanda Dale