Copper River Watershed Project’s Kate Morse leads tour of culverts near Cordova during an “atmospheric river” rainfall event. Jessica Cherry

Copper River Watershed Project’s Kate Morse leads tour of culverts near Cordova during an “atmospheric river” rainfall event. Jessica Cherry

by Jessica Cherry

Summer 2023, FORUM Magazine

THE TERM "BLUE ECONOMY" refers to a vision for sustainable use of ocean resources, but it’s also true that for years now, by most measures, Alaska’s larger economy has had a stubborn case of “the blues.” The future of oil and gas extraction in our state is uncertain, due not only to its contribution to climate change, but also its role in international geopolitics. The loss of jobs and dividends from that sector has had clear impacts in our state, leaving questions about how to train our future workforce. The nature of our fisheries has also shifted, with low returns or outright crises in some populations, and booms in others. Keeping infrastructure functioning—roads, ports, pipelines--as the climate grows ever more extreme, poses its own expensive challenges. Last fall, I had the chance to travel around the Chugachmiut region, including Cordova, Valdez, and Seward, to learn and think about Alaska’s past and future choices, and the challenges for our Blue Economy. These are part of the traditional lands of the Chugach Sugpiaq and Eyak people, now modern cities trying to maintain ocean and urban infrastructure, healthy ecosystems, and highly trained employees.

Dr. Maile Branson, science director of the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute in Seward. Jessica Cherry

It’s mid-September and I’m standing in the Chugach National Forest with a dozen or so hydrologists and environmental managers, and we are experiencing what is called an atmospheric river, which is a fire hose of very heavy rainfall, pointed directly at the eastern part of Prince William Sound. Despite studying or even forecasting rain for a living, most of us are beginning to wonder if we are really wearing the right clothes for this tour of culverts led by the Copper River Watershed Project’s Kate Morse. This is a day for the sort of commercial grade foul weather gear a fisher would use; as Alaska’s Climate Services Director for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), I should have known better. Along the forest’s edges, the bright fall colors of the wetland shrubs and grasses are barely visible behind white sheets of rain.

Eastward from the city of Cordova, past Eyak Lake and its outlet the Eyak River, runs the Copper River Highway. The highway runs over the roadbed of what once was the 200-mile-long Copper River and Northwestern Railway, past the former Eyak village of Alaganik and half a dozen retreating glaciers, to the Million Dollar Bridge over the Copper River, and north to the Kennecott Mines near McCarthy. After millions of dollars of copper were extracted by companies led by J.P. Morgan and the Guggenheim family in the early Twentieth Century, the road that replaced it never made it much past mile 50. Damage from the 1964 earthquake slowed further roadbuilding. Then, in 2011, river migration and erosion took out another crossing at mile 36, past which now a traveler peers only onto the raging Copper River.

This highway is at the center of one controversy about Cordova’s future. On our field trip, Morse is showing us how the road forms a barrier to salmon crossing and spawning in this dynamic landscape of glaciers, forests, and wetlands. The area’s heavy rains have clogged the culverts, habitat has grown poor, and even some of the Alaska Department of Transportation’s culvert repairs have not restored fish habitat. Climate-driven changes in the number of extreme rainfall events will only move more gravel. Connecting Cordova to the rest of Alaska’s road system would require an enormous cost to build and maintain. In a budgetary environment where even marine ferry service to Cordova and surrounding communities has been reduced or suspended for months, it’s hard to imagine the road being built again past mile 36. The road does provide access for locals and visitors to subsist, recreate, and utilize “Mudhole” Smith Airport, all important to the predominantly fishing-based local economy.

When I meet with Samantha Greenwood, the city’s Public Works Manager, she talks about the way gravel makes its way into the storm sewer systems and how some of that infrastructure is a century old now. The water supply is another concern. Local fish processing requires a huge supply of fresh water, and during the 2019 drought that hit Southcentral Alaska, the city had to start to make choices. Greenwood and Clay Koplin, CEO of the Cordova Electric Cooperative, worry about the future of droughts in Cordova. Cordova gets about 70% of its electricity from hydropower. When creeks start to run dry, the utility has to burn more diesel fuel. While precipitation is projected to grow more intense, drought is also expected to increase in frequency and intensity; both are part of a trend toward a more extreme climate.

Offices have closed or been mothballed because they can’t keep employees in Alaska’s smaller towns.

Valdez might be what Cordova would look like if it was on the road system. I’ve flown into town on the heels of that same atmospheric river, but for a brief window the sky is bright with light reflecting on silvery cloud wisps. It’s hard not to notice the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) terminal from the airplane: a cluster of glistening white storage tanks on a hill in the harbor. But, crude oil production in Alaska peaked 35 years ago, the year before the supertanker Exxon Valdez ran aground on Bligh Reef, about 30 miles to the south of Valdez, spilling more than 10 million gallons of oil into the ocean and coastal ecosystems.

Now my husband is here, having driven from Anchorage, and for a couple of days we explore the area and I watch him fish cohos from the beach near the pipeline terminal. The rain returns, but it’s only a light mist and rainbows come and go, as black bears wander down the beach. In the evenings, we enjoy the breweries in town and even this gritty place makes a strong case for itself.

By now, Dr. Amanda Glazier, a professor from Prince William Sound College in Valdez, has contacted me; we’d met knee deep in a flooded culvert in Cordova, where her students were learning to take water flow measurements. She is running a new program to teach young people, mostly high schoolers, how to work as environmental technicians. I think this is a great idea and I’d like to help, but their current course load won’t qualify the students for the federal jobs my agency can’t seem to fill in places like Valdez. Offices have closed or been mothballed because they can’t keep employees in Alaska’s smaller towns. Despite years of deep funding cuts to our state’s university and community colleges, it’s clear that workforce training and retention are central to this region’s economic future.

The local cemetery seems like a natural stop on a quintessential autumn day. One monument written in Russian memorializes someone born shortly after Alaska’s sale in the mid-19th century. I’m reminded that not so long ago, the world was quite different, and Alaska’s Russian economy at that time was centered around the fur trade. Russian Orthodox crosses on new headstones show the long tail of that history. Out in the Bering Sea, the Northern fur seal populations, having never recovered from the Russian fur trade, are now in decline from a warming ocean impacting their food supply. The fur seals tell one story of ocean extraction gone horribly wrong. I hope our contemporary fisheries don’t suffer the same fate.

But here in Valdez the Steller sea lions are happy. With other late-season tourists, I watch them feed and fight at the outlet of the Solomon Gulch fish hatchery. In a gentle drizzle, my husband and I hike up the road to the Solomon Gulch dam and lake. Built just after the oil pipeline, this hydropower facility provides the majority of the power needed by the Copper Valley Electric Association. In fact, the penstock is made from left-over pipe from the TAPS. Someone had the foresight to make a lasting energy solution here.

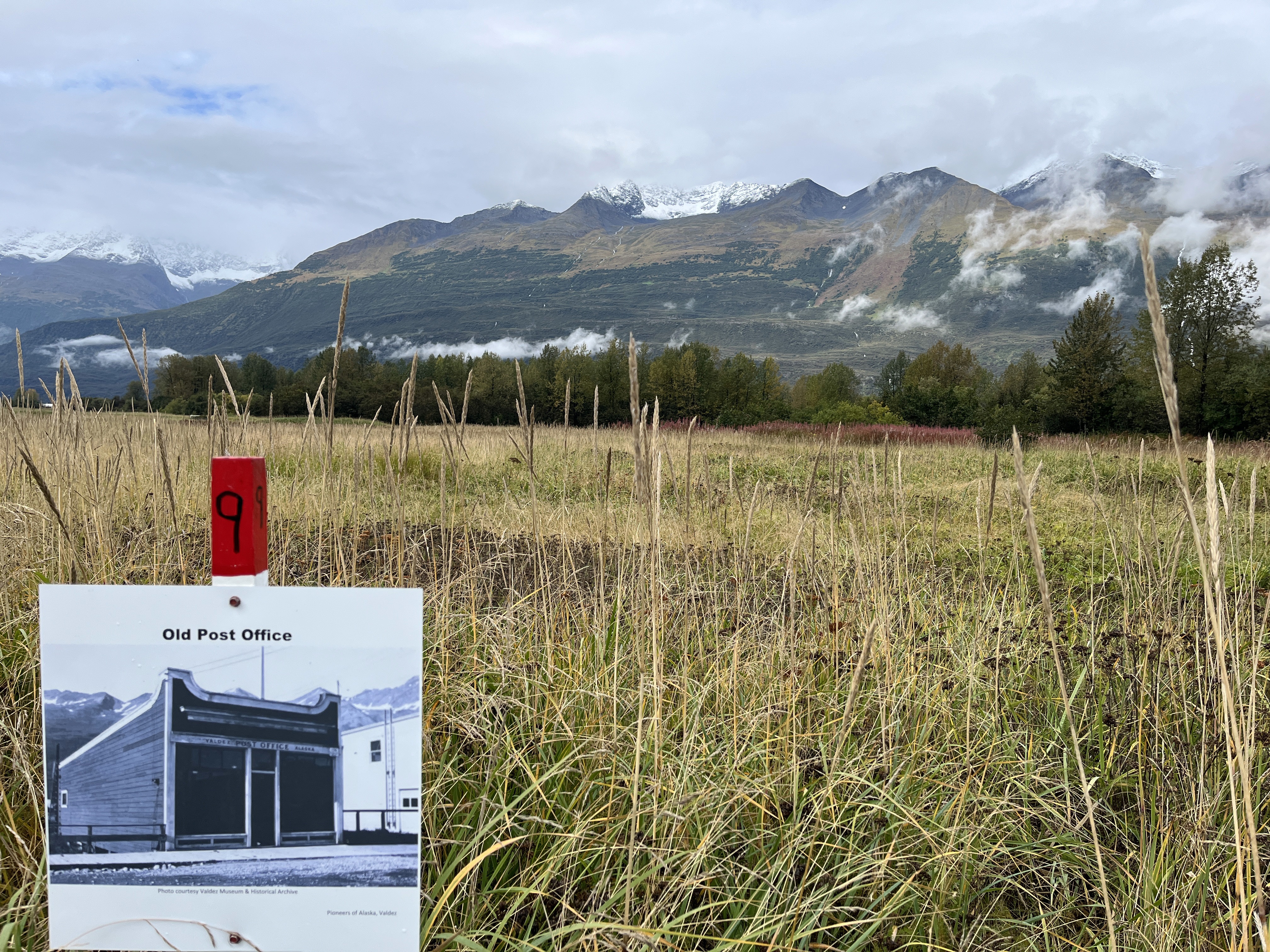

The old townsite is my last stop in Valdez before my flight will be delayed and canceled and delayed again by another atmospheric river. It’s eerie to see the townsite laid out in historic photographs before the 1964 earthquake, tsunami, and underwater landslide that claimed 32 lives here and 115 throughout Alaska. Accounts describe the water being sucked out of the Valdez harbor. Nearly all who died drowned. We hope our training drills and Tsunami warning sirens will save lives next time. The rapid recession of Barry Glacier in western Prince William Sound makes climate change-induced landslides a possible mechanism for future tsunamis. Today, though, the ocean looks innocent and at the edge of this marsh and a hundred gulls swarm around a pier of rusting waste.

University of Alaska Fairbanks’ research vessel Sikuliaq

docked near Lowell Point in Seward. Jessica Cherry

The old townsite in Valdez. Jessica Cherry

Seward is my last stop on this particular wander and I see the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ research vessel Sikuliaq docked. It brings back memories of my time at sea on other research vessels, long before this one was born. Each summer, the northern seas are crisscrossed by not only commercial, military, and tourist vessels, but also a whole science research economy out of the U.S., Russia, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, and now China. A few months ago, a landslide let loose behind the Sikuliaq’s dock, at nearby Lowell Point. Amazingly, no one was hurt, but the only road to the small community of Lowell Point was blocked for some time.

On a prior visit, I’d been briefed by the borough’s Seward-based flood service area manager Stephanie Presley about local mechanisms for flooding. “Seward doesn’t so much have a flooding problem as it does a gravel problem.” Ah, yes, gravel again. And whole new extremes in heavy precipitation pushing it around. Because of an avalanche threat in Turnagain Pass, I once missed a tour of the newly flushed Lowell Creek Tunnel, a project by the US Army Corps of Engineers that diverts water from downtown Seward through a mountain, and of course that tunnel fills with gravel. The Resurrection River, Exit Creek, Japanese Creek, Sawmill Creek and others are all gravel factories left behind by glacial retreat. Some might argue that a reliable gravel supply is the basis of a modern economy, but it’s possible that Seward has too much of a good thing.

“Seward doesn’t so much have a flooding problem as it does a gravel problem.” Ah, yes, gravel again.

Finally, I visit the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute to talk to Dr. Maile Branson, the science director. With her foot rocking her sleeping baby’s carrier, we chat about the mariculture and kelp farming programs that APMI is leading. She takes me on a tour of the shellfish tanks and explains how they are helping replace stocks of local indigenous foods. She shows me the ocean acidification lab and the cultures of harmful algae, whose blooms are responsible for shellfish poisoning. Branson and the other staff explain the kelp inoculation process in the seawater tanks. A farmer-intern shows me the growing kelp under a microscope. This is incredible. And hopeful. But it’s also hard to imagine the effort and capital it would take to scale this potential new industry to “Alaska sized.” Just a stone’s throw from the Lowell Creek Tunnel outlet, Branson complains about the gravel clogging APMI’s sea water intakes. It’s not cheap to run a lab in this environment. Maybe by the time her baby is grown, the incentives for more investment in sustainable ways of life will be there. For almost certainly, the oil will be gone.

Traveling around parts of Prince William Sound—Chugachmiut--I’ve learned more about this dynamic environment and the resilient people who live and work here. A meaningful vision for a Blue Economy must acknowledge the changing conditions in the ocean and the atmosphere: generally, a warmer, more acidic ocean, and more extreme swings in precipitation. Critical fish habitat, where it’s disrupted by human infrastructure and industries, needs to be restored and maintained, for fish and shellfish to thrive again. Regulations for sustainable harvesting of ocean resources must account for changing ecosystems. There needs to be ongoing investment in local opportunities for education and workforce development, and reliable air and ferry service. Residents need to be prepared for other large earthquakes and tsunamis. Across Alaska, we’ll have to build and expand sustainable municipal and marine energy systems, to meet the demands of local economies. Finally, ongoing investments in ocean research will reveal new understanding and, potentially, whole new ways of life. ■

Jessica Cherry is a geoscientist, writer, and photographer living in Anchorage. She currently serves as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) Regional Climate Services Director for Alaska, but all opinions expressed here are her own. More at freshandsalty.org.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

November 13, 2025 • MoHagani Magnetek & Polly Carr

November 12, 2025 • Becky Strub

November 10, 2025 • Jim LaBelle, Sr. & Amanda Dale