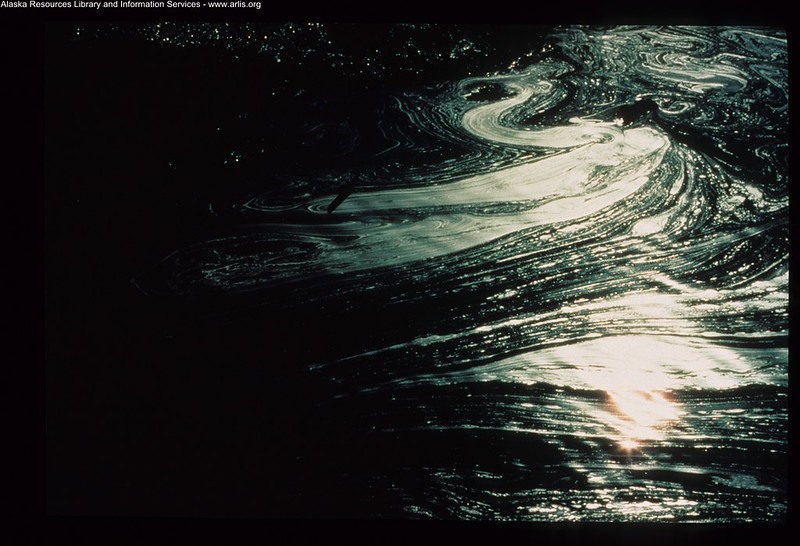

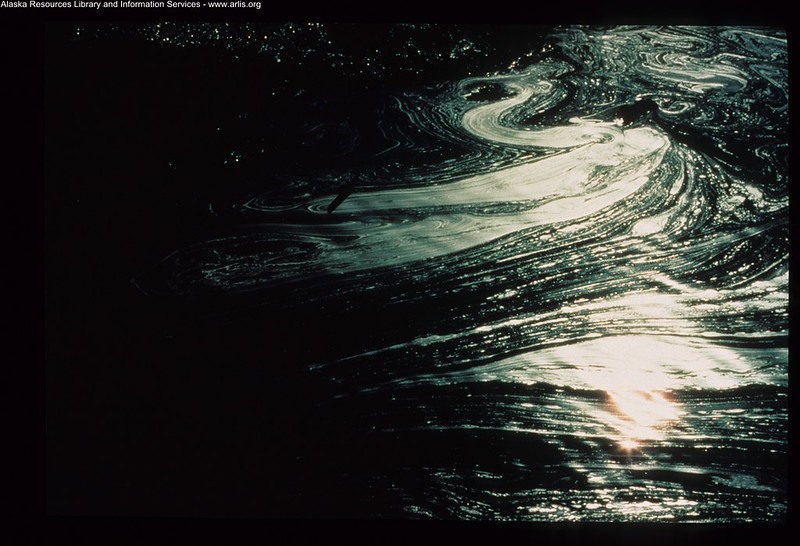

A iridescent oil sheen on the water in Prince William Sound after the spill Photo credit: Alaska Center for the Environment Exxon Valdez Photo Collection, ACE4, Alaska Resources Library & Information Services

A iridescent oil sheen on the water in Prince William Sound after the spill Photo credit: Alaska Center for the Environment Exxon Valdez Photo Collection, ACE4, Alaska Resources Library & Information Services

By Robin McKnight

Winter 2024-25, FORUM Magazine

THIS IS WHAT I IMAGINE: a dark shape in the water, the color of an Indigo snake under the sun. The slow sludge, molasses in its movement, warm as hot fudge. A creeping black vine, sinister and sentient. It is something from the Goosebumps books of my childhood, pages soft from small fingers turning them in anticipation of the next horror, the next jump scare, the next unidentified danger. This is that scary story brought to life, creating ghosts that haunt a familiar coastline, wraiths between the drooping boughs of spruce trees, or hiding in the shadows of a harbor many of us know by name.

I imagine the high note of an orca’s whistle, the muted flap of a white wing dipped in ink, the raucous of sea lions from atop a salt-sprayed rock, and the intermittent static of the radio. Then, I imagine silence.

__

IN 2015, I was in college, thousands of miles away from my home in coastal Alaska, in a place where it is possible to spot the iridescent sheen of an Eastern Indigo snake as it seeks shade beneath a palmetto. I had never lived further away from the ocean, and yet, it was only a forty-five-minute drive to the sand and soupy, slow waters of the Gulf of Mexico. I was often claustrophobic in the humidity, the traffic, staving off panic attacks and the ache of homesickness by picturing the cold, unrelenting waters of the Gulf of Alaska, the sharp slope of a fjord, and the watercolor blue of glacial ice.

I don’t remember much about this first semester. There are soft-edged memories that play out like a coming-of-age movie: a teary phone call home, a new boyfriend, a dark bar, a football game. What I recall with the most clarity, and perhaps unsurprisingly, is any mention of Alaska, finding comfort in the familiar in an unfamiliar place.

I was too preoccupied with recognition, a memory of mine that was not mine at all but that of a collective experience nearly a decade before I was born.

I learned something obvious: a lot of people know nothing about Alaska beyond the reality TV shine of our tourism industry, often summarized through out-of-focus photos of bears and mountains in a family group chat. What they know outside of this hazy impression of place is all about the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

During my first week of classes, in an auditorium of nearly two hundred students, a professor displayed a photo of the oil tanker aground at Bligh Reef, followed by a picture of disembodied, gloved hands, and a gull, delicate-boned and drenched in the pitch of dark crude oil, gingerly held between them. “Hello,” that tar-feathered bird seemed to say to me, long dead and projected on screen through my professor’s use of Google Images. Hello, I thought. My heart leaped because I knew this, I understood this. I barely heard the instructor discuss the details: 11 million gallons, Hazelwood, loss of species, disaster response. Something like that. I was too preoccupied with recognition, a memory of mine that was not mine at all but that of a collective experience nearly a decade before I was born.

The oil spill is the current that runs through every community in coastal Alaska. The immediate environmental and socio-economic effects were devastating, and the prolonged impacts continue to this day. Fisheries collapsed, subsistence resources declined, and entire ecosystems faltered, like a missed step descending the stairs. Communities changed. It was the type of change that was visible, in the water, on the coast, and the type of change so irrevocable it could be seen in the faces of children, and grandchildren. It was the kind of change that was reflective, a mirror for not only what was, but also what was to come.

In the auditorium, students around me murmured, empathetic hums for a creature that suffered at the end of its short life. When I looked at the photo all I saw was home and I smiled.

A spill responder holds a bird covered in oil Photo credit: Alaska Center for the Environment Exxon Valdez Photo Collection, ACE9, Alaska Resources Library & Information Services

THIS IS WHAT I IMAGINE in the moments, weeks, months after the spill: orange Grundens, a curse as someone slips over an oiled rock, their Xtratuff finding purchase in a shallow, brackish pool near the sea. I imagine tears and I imagine fear. I think of sweating in rain gear aboard the deck of a small boat, springtime rain, the only clean thing for miles, and someone with their eyes closed, face tilted towards the sky. I imagine shock, disbelief, phone calls, and a heavy wooden table in a courtroom.

There are many things that I cannot imagine at all. The sound of a ship that size running aground, the smell of the Sound afterward. Did it smell like benzene, sickly and sweet? Or artificial, the scent of plastic wrap, chemical preservatives? Putrid, acrid, rotten?

Other details are simply unfathomable; I cannot imagine the loss. A quarter of a million seabirds, thousands and thousands of sea otters, seals, sea lions, the herring eggs. The fish. Mussels in shades of pearl and navy peeled off rocks, ash, and dust. There is a loss so great that the numbers are unreachable and a loss so devastating that it alters timelines. I cannot imagine the urgency.

I turn these fictions I’ve created about the spill over and over in my mind, and the looking glass becomes duller in this ocean until it is transmutable and pedantic. It is only within the context of actual memory, the stories I’ve heard from Elders, community members, and researchers, the first-hand photos, the oral histories, that I can picture Prince William Sound, an Alaska, before the spill. I’ve only ever known the impacts.

But you. You may have been there. You could have worried about the clams and seals, the fisheries, your community. You may have been a part of clean-up efforts, the great stretch of boons across the Sound. You may have seen your father's head in his hands, stress written across your mother’s brow. Many carry this with them now. There is more to this, so much that I will never know. Buried beneath the sand, it’s possible to still find oil, even now, a memorial embedded in the land, in the waters. Thirty-five years later and the cascading impacts of the spill continue.

A seiner and tender in Prince William Sound Photo credit: Seth Brewi, 2019

THE SPILL IS THE REFERENCE POINT for all I understand about the place I grew up in, the place I call home. So for me, Exxon Valdez is not as much about memory as it is about identity. It’s in my work, the way I understand conservation, the way I define health. It’s as essential to my identity as a childhood best friend, distant and dreamlike yet fundamental.

When I was a child or in school, far away on a different coastline, between new mountains, or right at home, somewhere between Aialik Bay and Seward, I didn’t think much about Exxon Valdez. My family was not dependent on the resources of the Sound or connected to the oil industry through work, so it did not occur to me that I could be affected by the oil spill. That is a privilege. It’s also not true. It is true that as teachers, my parents did not fear for their livelihoods, their homes, or their futures when so many people in the Chugach region and beyond felt the impact of the spill immediately, and intimately.

The oil spill precedes me, my brother, my partner, my friends, and even my mother moving to Alaska, but it has shaped most of my life. The criminal funds from Exxon Valdez paid for the building I now work in. The research funded by the Trustee Council has shaped the way I understand the land I live on, and the health of the ocean that we all depend on. When I was six, my mother helped me bake a pumpkin pie, which won first place in a pie contest at a community event at the Alaska SeaLife Center. I think of my sugar-sticky fingers reaching toward rockfish and crab and harbor seals, sanctuaries behind thick windows of aquarium glass. Settlement funds built that space, the center’s research programs, and the many other aquariums and tanks that house thousands of small beating hearts.

Recently, I have felt as if there is a drop of crude oil in me, and yet it also feels as if I am carrying something heavier, and denser than water.

It didn’t occur to me while I was in my first week of college classes, missing home, listening to an academic who wasn’t from Alaska discuss the relationship between the oil and gas industry and what happened that day in 1989. It didn’t occur to me as a child, but rather by listening to the people from my region -- from Prince William Sound, from Cook Inlet. It is only with the resilience and knowledge of the Sugpiat and Eyak People that the region flourishes, and that recovery is possible. It is only with the response of those on the scene that the Sound, Kenai Fjords, and the Outer Coast, have anything left at all. It is this legacy that I find myself a part of now. The collective memory that Exxon Valdez left behind is not only one of devastation but also of spirit, complexity, and catalyst. It is not one story but many, and all of them matter. The berries I pick in the fall. My partner’s first season seining, fishing with a large vertical net hanging down into the water, for salmon in the Sound. The sealion stew was shared with me last fall. The last of the Chugach Transients dipping beneath the swell, unexpected in Resurrection Bay.

I cannot understand an Alaska before Exxon Valdez but I know the outcomes as well as I know the sound of waves meeting the shoreline: innately. I spent so much time trying to imagine myself at the scene of the spill, but there is more than imagination. The spill is a throughline in my life. Its fallout is like a meteor shower, its origin point fracturing into different directions that illuminate the past with half-dead light. Recently, I have felt as if there is a drop of crude oil in me, and yet it also feels as if I am carrying something heavier, and denser than water. It is with this awareness that I try to place myself into the context of the spill. Not to imagine what

it was like, but to see how it is now, thirty-five years later.

Maybe I can learn to reach my hand both backward and forward in this space, to hold tight to the guidance from the people of the region, and to continue through unknown waters towards a bright horizon. ■

Learn more at the Project Jukebox Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Project.

References

Alaska Center for the Environment. (2010). ACE4. ARLIS Reference. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/arlis-reference/5012687989/in/album-72157625007158526.

Alaska Center for the Environment. (2010). ACE9. ARLIS Reference. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/arlis-reference/5012702241/in/album-72157625007158526/.

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. Alaska Resources Library & Information Services. (2024, February 9). https://www.arlis.org/collecti...;

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council. (2024, April 23). https://www.pwsrcac.org/about/...;

Personal stories from the Exxon Valdez Disaster. Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council. (2024, March 23). https://www.pwsrcac.org/outrea...;

Saulitis, E. (2013). Into great silence: A memoir of Discovery and loss among Vanishing Orcas. Beacon Press.

University of Alaska Fairbanks. (n.d.). Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Project Jukebox. Project Jukebox. https://jukebox.uaf.edu/exxonv...;

Robin McKnight is an Education Specialist & Science Communicator, amateur birder, and poetry enthusiast. She is always down to go tidepooling. Robin is a 2024 FORUM Writing Fellow.

FORUM is a publication of the Alaska Humanities Forum. FORUM aims to increase public understanding of and participation in the humanities. The views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the editorial staff or the Alaska Humanities Forum.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

November 13, 2025 • MoHagani Magnetek & Polly Carr

November 12, 2025 • Becky Strub

November 10, 2025 • Jim LaBelle, Sr. & Amanda Dale